Share Twitter Facebook Email Copy URL

There will be no climate change conference in 2020—but our future is nevertheless being negotiated

Nadja Charaby is Head of the International Politics and North America Unit at the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung as well as an advisor for climate policy. Tetet Lauron is a Filipino climate activist, she is involved in the People’s Movement on Climate Change and Climate Justice Now! She also works for the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung. Katja Voigt is project manager for climate policy and North America at the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung.

The 26th UN climate change conference, COP26, should be taking place now in Glasgow. It was postponed due to coronavirus. Has the struggle to develop adequate climate change policies come to a standstill? No, but it has become more difficult, as governments are now fighting to prevent their own public health and economic crises from escalating.

First, the good news of 2020. To begin with, the sweeping measures and economic relief funds have demonstrated that, when necessary, government can rapidly enact drastic measures in response to a crisis. Secondly, all over the world people have been demanding that the climate crisis not be drowned out by the public health and emerging economic crises, and that they be understood as consequences of the same devastating logic of growth, competition and profit on which our economic system is based. And thirdly, to a certain—if insufficient—extent, there has been limited debate about the climate compatibility of new public aid programmes. Climate change is present in the pandemic, if only at the discursive level.

But in 2020 the field is in fact more complex than ever. A major stocktake should have been on the COP26 agenda. Five years have passed since the Paris climate conference and governments are supposed to be strengthening their pledges in order to prevent a catastrophic destabilization of the global climate. As it stands, temperatures are expected to rise by 3.2 degrees Celsius and more; the Paris climate goal is attainable only if we succeed in cutting global emissions by 7.6 percent every year. We are far from achieving this—despite the short-term dent that the coronavirus has made in the global emissions curve. Governments in the Global North should now be unveiling plans to mobilize 100 billion US dollars for climate protection and adaptation in the Global South. But that is already a long-outdated goal. The countries of the Global South are rightly demanding much more comprehensive funding for climate adaptation, compensation for damages and losses, and climate protection measures.

COVID-19 Hits Countries with Varying Degrees of Severity

The pandemic is putting the UN system—which was already cumbersome and under attack by right-wing populist governments—to the test. The UN Climate Change Secretariat is now tasked with seeing that negotiations proceed, while individual governments seek primarily national solutions to the crisis. The coronavirus pandemic is revealing how variously prepared countries are for the major interconnected ecological and social crises of our day. COVID-19 is affecting countries and individuals with varying degrees of severity and threatening the livelihoods of the poorest, who are unable to work. We have seen an uptick in violence, particularly against women. In many countries it is impacting people who already are simply trying to survive in an environment that has been thrown off course by drought, flooding, or locust outbreaks. While wealthy countries are unrolling sweeping economic stimulus packages, COVID-19 is making poorer countries even more vulnerable and exacerbating the mix of poverty, inequality, hardship, and climate crisis.

Europe’s current refusal to accept refugees from camps located on its borders is only the latest devastating example of the Global North’s isolationism. The dire situation calls for quick, uncomplicated measures that would grant them freedom of movement and a life of dignity. Current European migration policy clearly demonstrates that the struggle to establish well-regulated and humane policies for taking in individuals compelled to migrate for climate-related reasons is, and will increasingly continue to be, a protracted one. The same applies to an additional core demand in the run-up to COP26: an independent, easily accessible fund to compensate for climate-related damages and losses.

There is no denying it: in light of the millions of people already impacted by the climate crisis, a year’s delay in international climate diplomacy is significant. Our remaining leeway for greenhouse gas emissions is rapidly dwindling, and 2020 has seen the force of the climate crisis becoming ever more palpable in tremendous wildfires, Arctic melt occurring later than ever, new droughts, floods, and typhoons.

Digital Formats to Replace Meetings in Glasgow

This year the UN Climate Change Secretariat is using alternative platforms to try to build international momentum for more climate protection measures. The task is anything but easy considering that, due to COVID-19, most governments are absorbed with developing short-term national and regional emergency programmes. After testing a series of online events over the summer, called June Momentum, the UN will host the virtual Race to Zero November Dialogues in early November, as part of the Race to Zero Campaign. The goal is to bring together both nongovernmental actors, city and regional representatives, as well as companies and investors, in order to identify strategic areas for transforming both the economy and society, and establish networks for green investment and the development of sustainable infrastructure. The vague hope is that, in the end, these conversations will encourage countries to increase their climate targets.

A prominent UN platform is thus providing a framework to further develop the dangerous narrative of net-zero emissions. After all, those involved in the Race to Zero Campaign are committing, not to zero, but to net-zeroemissions. This deceptive terminology makes it easy for governments and businesses to further delay taking effective measures. For if we nurture the illusion that it will one day be possible to remove huge amounts of CO2 from the environment, for example using BECCS technology, radical environmental change appears less urgent. In addition, net-zero climate targets further perpetrate a colonialist mindset, because the Global South is for the most part seen as the provider of vast plots of land needed for tree plantations. Not to mention the fact that the planned discussion series feeds the narrative—and naïve promise—of “inclusive sustainable growth”. The most important issues—the redistribution of global wealth as the most effective solution to multiple crises, the legitimate demands of those hardest hit by climate change, and putting an end to the logic of growth and dirty and exploitative business models—are not even on the agenda.

According to their statement, the UN Climate Change Secretariat’s subsequent event, to be held from late November to early December, is also primarily aimed at highlighting positive examples and success stories from 2020, and keeping up the positive momentum. The UNFCCC Climate Change Dialogues are designed to identify topics that are suitable for preparing the intergovernmental negotiation process in the coming year. It is unclear how governments will use the platform. The explosive topics remain on the table, but the digital format is likely to hinder any serious discussions.

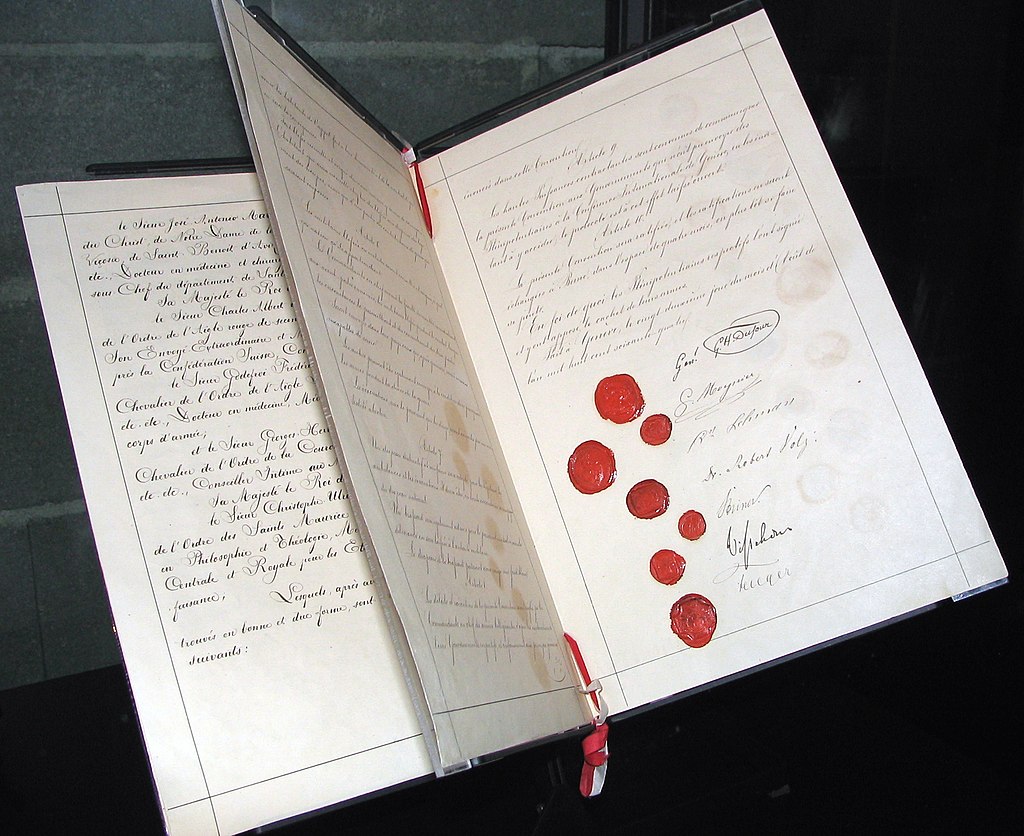

Among other things, the controversial Article 6 of the Paris Agreement is still on hold. Intended to regulate international carbon trading, it has threatened to blow up negotiations on several occasions already. Critics of Article 6 see it not only as a dangerous gateway to double-counting credit reductions, but also as a selling of indulgences that would enable rich countries to continue avoiding any genuine transformation. The establishment of CO2 trading under the Paris Treaty and the “false solutions” promoted by this framework would threaten the rights of indigenous communities—above all the right to self-determination—as well as environmental protection standards and the protection of biodiversity.The major players who are attempting to establish themselves with so-called “nature-based solutions” to climate change meanwhile continue getting into position. On the one hand, behind this ambiguous term are indeed many serious approaches that aim to revolutionize the way we think about preserving biodiversity, protecting forests, and managing farmland, from natural to agroecological methods. But at the same time, large corporations are misusing the term in order to promote “climate-smart agriculture” and offset mechanisms as new business models.

A Climate-Friendly Way Out of the Crisis?

Actors with diverse interests are all now striving for a climate positive recovery from the present health and economic crisis. The opportunity is enormous: huge sums of money are already being moved around; the world could thus create sustainable infrastructures and restructure economic sectors in a very short time frame. However, there is a serious risk that governments will continue to stand behind the questionable old argument—that fossil fuels are cheaper—in order to revive their economies.

Activists from the Global South are now also increasingly warning against another supposed solution: so-called “debt-for-environment swaps”. A bit of background: because of the additional burdens of the coronavirus pandemic, the Global South needs more financial resources to cover its basic needs and make substantial expenditures. But these governments are already paying off significant debts—under creditors’ strict conditions, which perpetuate the vicious circle of structural adjustment programmes and austerity policies. They have indeed been suspended thanks to the Debt Service Suspension Initiative, but not cancelled. That’s where the debt-for-environment swaps come in: a country finances climate protection measures locally and is relieved of a portion of its external debt in return. The logic behind this is thorny. How does one offset the conservation of a forest against a debt? Moreover, the rights of indigenous communities are at risk of being violated, as is so often the case, for example by being driven off their ancestral land for the sake of climate protection projects.

Social Movements: Seizing the Crisis As an Opportunity

Thanks to the pandemic, it is now clearer than ever that we are in dire need of solutions to the multiple crises and injustices of our day. By necessity, social movements have shifted a great deal of their protest activity into the digital realm. Activists, groups, communities, and NGOs are all working to bring their concrete demands for a more social, just, and sustainable world into the debate on how to best handle the coronavirus. From webinars, workshops, and meetings to full-blown conferences and climate camps, as well as social media campaigns across all channels, online platforms are being used to organize protests, interference, and political activities. What is more, many formats are now accessible to a much wider audience thanks to digitalization—a new normal which fosters international networking.

From mid-October to mid-December, the Climate Action Network is running the #WorldWeWant campaign, which gathers and promotes stories about the effects of the climate crisis and draws attention to people who are holding their national governments to account. And from 12 to 16 November the climate justice movement will come together at From the Ground Up: Global Gathering for Climate Justice. The goal is to promote strategic networking and exchange on a wide range of topics.

The following video summarizes the recent message of many climate activists in a wonderful, encouraging, and at the same time combative way: let us use this crisis as an opportunity to show solidarity and implement the long-recognized solutions for the multiple crises of our time.

Translated by Caroline Schmidt and Marty Hiatt for Gegensatz Translation Collective