Share Twitter Facebook Email Copy URL

Anti-Muslim politicians in the northeast Indian state of Assam wanted to use a new register of citizens to trigger the mass deportation of Muslims to neighbouring Bangladesh. But most of the people affected turned out to be Hindus.

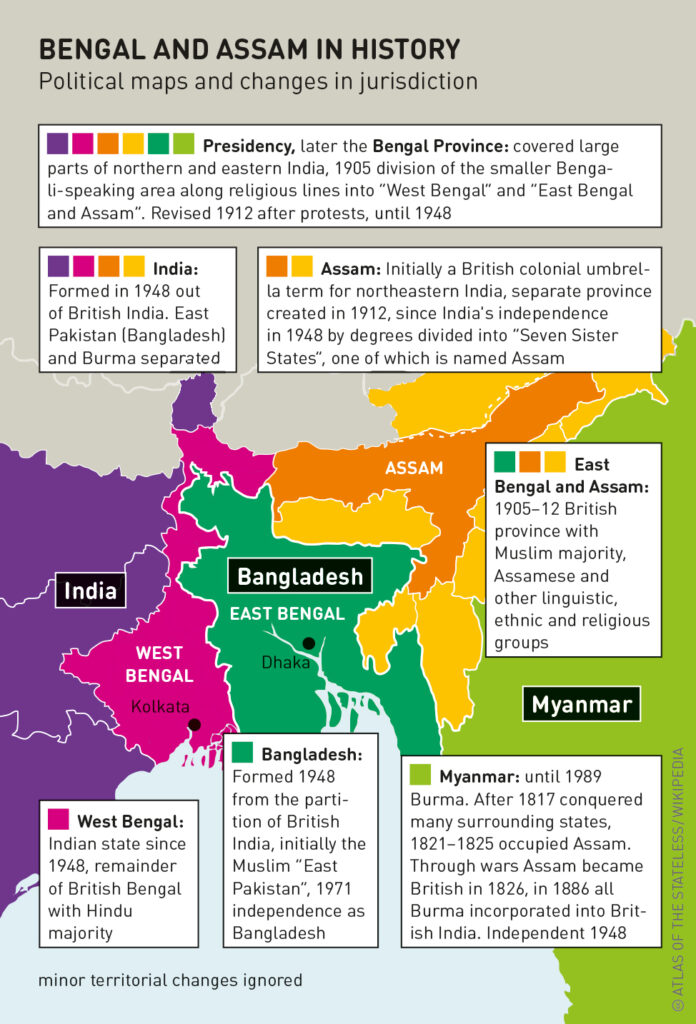

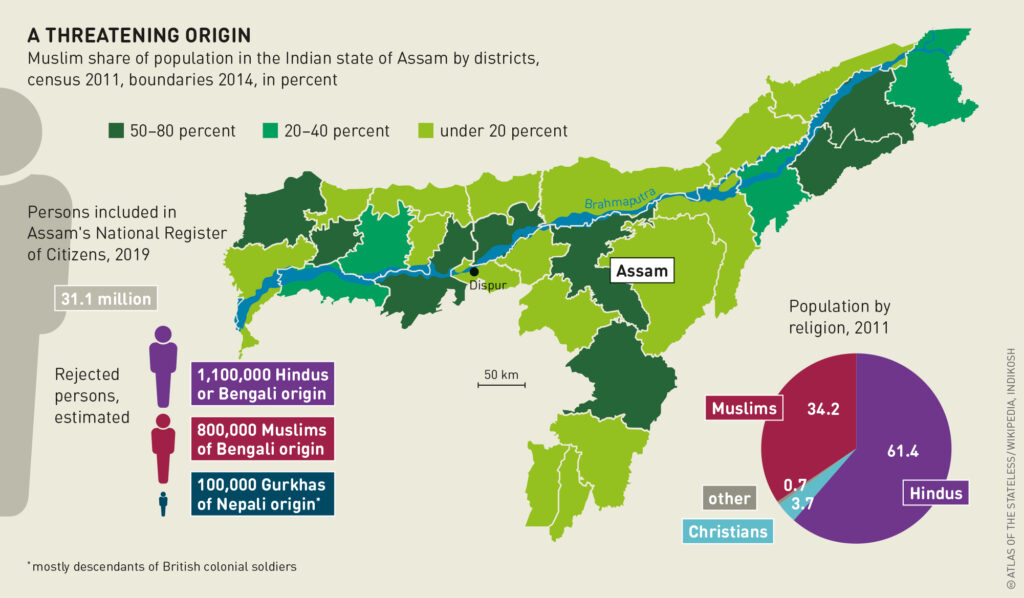

Nearly two million people in Assam in northeastern India, mostly Bengali Hindus and Muslims, are currently at risk of losing their Indian citizenship because their names do not appear in the updated National Register of Citizens. This comprehensive register for Indian citizens in Assam, was launched in 1951 when Assamese leaders refused large-scale settlement for Hindu refugees fleeing East Pakistan after the partition of India.

The Register was updated in 2015 following an order from the Supreme Court of India to the federal and Assam state governments. The trigger for this process was a Public Interest Litigation filed by Abhijeet Sharma, director of Assam Public Works, with India’s Supreme Court. The aim was to mandate the government of Assam to update the Register in view of the “enormity” of illegal migration from Bangladesh into Assam, thus facilitating the identification and deportation of such migrants who did not “qualify as citizens”. Ranjan Gogoi, an ethnic Assamese who later became India’s Chief Justice, was on the Supreme Court bench that issued the order.

The problem was and is not only about Muslim migrants. Some ethnic Assamese groups and the local Assam bureaucracy want all migrants and descendants of migrants from Bangladesh and Nepal, whether Hindu or Muslim, to be excluded, because they are afraid of being reduced to a minority in the state. Of the 32.9 million residents of Assam who applied for inclusion in the Register, nearly two million were excluded: more than one million Bengali Hindus, half a million Muslims of Bengali origin, and 100,000 Nepali-speaking Gurkhas, mostly Hindus and Buddhists. The “cut-off date” for decisions on the citizenship status in Assam for immigrants from Nepal and present-day Bangladesh was 25 March 1971, the day the Bangladesh Liberation War began. This date was determined in the Assam Accord of 1985, which was signed between the Indian government and ethnic Assamese student groups, following violent protests in 1979–85 demanding the expulsion of all illegal migrants.If someone is excluded from the Register, this is not the end of the road. Excluded individuals can appeal to Foreigners’ Tribunals that have existed in the state since 1985.

If the Tribunal decides that they fail to qualify for inclusion in the Register, they risk losing their citizenship and becoming stateless. However, judicial processes in India are long and drawn out, and people who are not on the Register complain that they are harassed by the police and Assamese vigilantes because of their unclear status. The construction of several new large detention centres in Assam and elsewhere in India has raised fears that those identified as illegal migrants will end up in prison. Nearly 60 Bengali Hindus and Muslims have already committed suicide after they were excluded from the Register; nearly 30 have died of trauma and diseases in the detention centres. Analysts compare the situation in Assam with that in Myanmar’s Rakhine state, where more than a million Rohingya Muslims suff er statelessness and face state-sponsored violence.

citizenship and migration are rooted in borders drawn

along religious lines by the British colonial administration

The updating of the Register in Assam has attracted widespread criticism, albeit for different reasons. Ethnic minorities such as Bengali – both Hindus and Muslims – are critical because they feel the process was discriminatory and high-handed. Assamese regional groups are upset because they feel more people should have been excluded and that many illegals have made their way onto the Register using fake documents. India’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government welcomed the updating implemented by the Supreme Court as a pilot project to be replicated all over India to “rid the country of illegal migrants”. However, it says the process was faulty because it excluded more Bengali Hindus than Muslims. Since the BJP is committed to protecting Hindus, it has passed a bill that amends the Indian Citizenship Act of 1955 seeking to provide Indian citizenship to all non-Muslim migrants from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan if they entered the country before 31 December 2014.

and rice. Nationalist groups in Assam now want as

many of their descendants as possible to leave

After the amendment to the Indian Citizenship Act in December 2019, angry Assamese mobs protested against granting citizenship to Hindu migrants “through the back door”. Indian opposition parties oppose both the new citizenship law and the BJP’s plans for a pan-India Register. Backed by student groups at nearly 40 universities, they allege the new citizenship law undermines the “secular edifice” of Indian polity as it privileges certain religious identities in awarding citizenship. They describe the plans for a pan-India Register as part of the BJP’s anti-Muslim agenda to deprive all Muslims of citizenship. Violent protests have erupted across the country, especially in Delhi and West Bengal. Altogether, the update of the Register threatens to create a huge problem of statelessness that could undermine India’s image as a vibrant democracy. If the government extends this exercise to other parts of India, it could also threaten the country’s relations with friendly neighbours like Bangladesh.

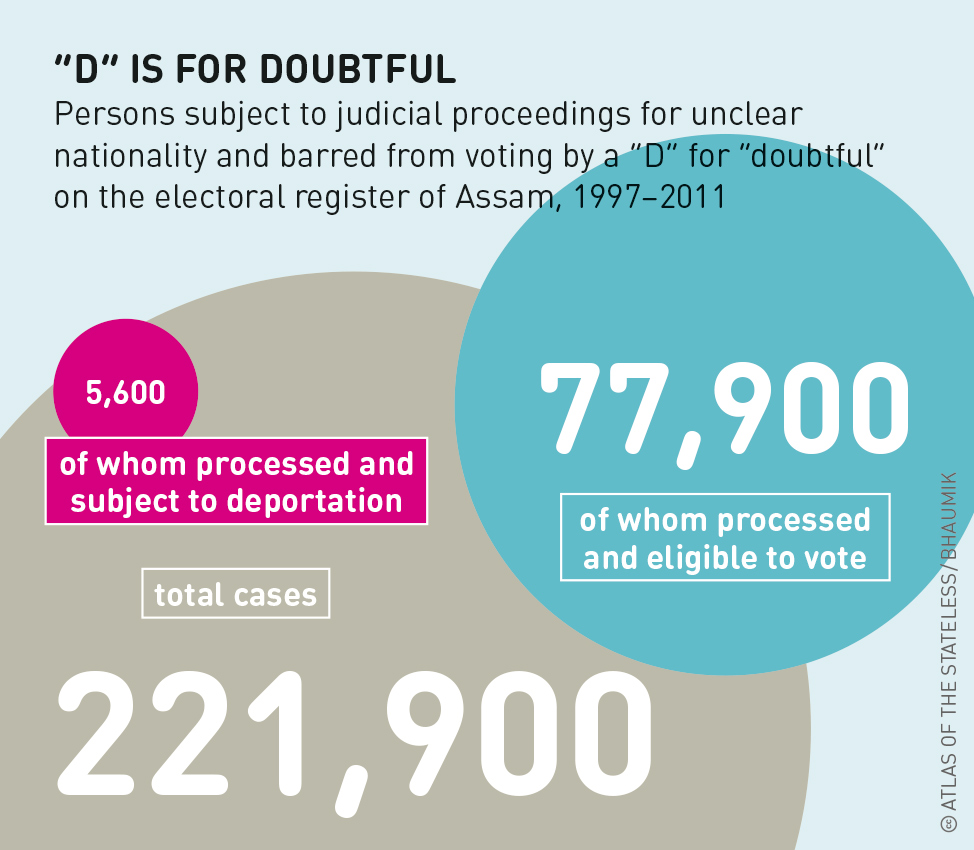

one-third of the cases. Result: 93.5 percent of the

people processed should have been eligible to vote

This contribution is licensed under the following copyright licence: CC-BY 4.0

The article was published in the Atlas of the Stateless in English, French, and German.