Share Twitter Facebook Email Copy URL

In Iraq, people have been left stateless because of successive waves of conflicts and injustices. Some groups have suffered a long history of discrimination; others have been rendered stateless by more recent events. Laws that discriminate against women are a special problem – but would be easy to fix.

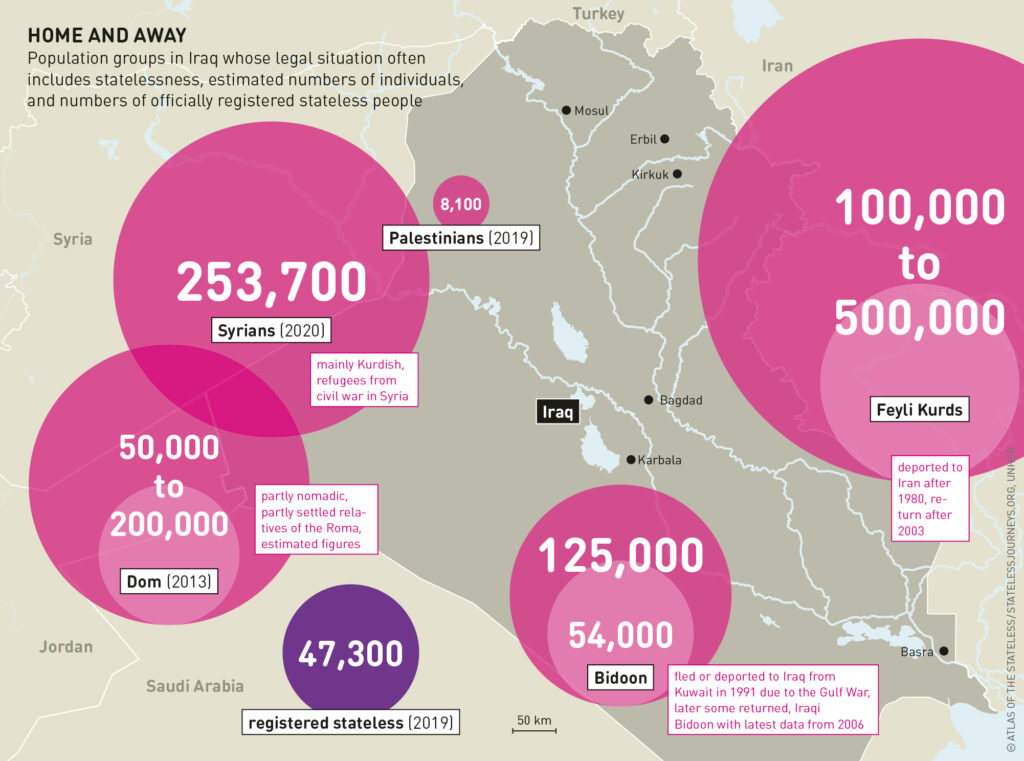

Since its independence from Britain in 1932, Iraq has been home to large stateless communities. This is mainly due to legal inequities, displacement that has persisted over several generations, and a series of conflicts, creating an environment that makes it difficult to address the issue. The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) records 47,515 stateless individuals in the country. The actual number could be considerably higher and may even rise further as a result of recent events. Reasons for statelessness in Iraq include flaws in the 2006 Nationality Law, predominantly Article 4, which does not allow Iraqi mothers to transfer their nationality to children who were born outside the country. This means that female emigrants and refugees must prove their children are descended from an Iraqi man if they are to be granted citizenship. Obtaining such proof can be very difficult.

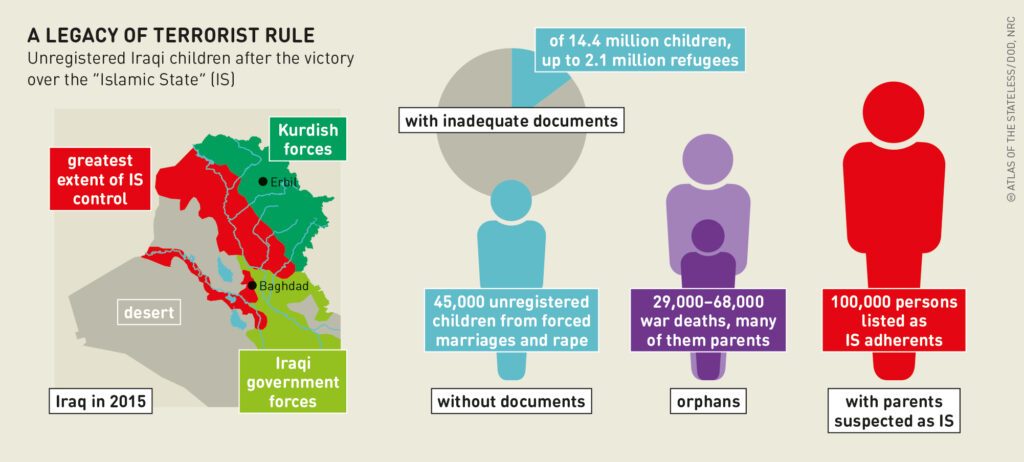

In addition, civil registration poses legal and practical challenges. Every Iraqi governorate has its own civil registration system, and these are complicated to navigate, especially for displaced people. As a result, many displaced Iraqis have not been able to access procedures such as birth and marriage registration; this puts children at risk of not being able to establish their legal identity. It is believed that over 45,000 children living in camps in Iraq do not have birth certificates issued by the Iraqi authorities.

Some people with Iraqi nationality hold documents that are no longer valid or that are not recognized by the authorities. This is particularly true for documents issued in areas previously controlled by Daesh, the so called Islamic State. Children of Iraqi mothers, including Yazidi women, who were either married to or raped by men connected to Daesh are at risk of being left stateless. So too are children born under Daesh control. Attempts have been made to regularize their situation, such as exchanging Daesh-issued birth certificates for government equivalents. But challenges remain: fathers, for instance, need security clearances before birth certificates can be issued.

years after the demise of the

“Islamic State”, many children are still not safe

Historically, displacement has contributed to statelessness in Iraq. The Faili Kurds, an ethnic group inhabiting both sides of the Zagros mountains along the Iraq–Iran border, were denied Iraqi nationality. In 1980, in the spirit of pan-Arab nationalism as well as anti-Kurd and anti-Shia ideological waves, the government of Saddam Hussein implemented Resolution 666. This stipulated that Iraqi nationality would be dropped for any Iraqi of foreign origin if it appeared that he or she was not loyal to the Iraqi homeland and people, and the objectives of the revolution. As a result, hundreds of thousands of Faili Kurds were denaturalized, arrested and deported to Iran, where they were equally unable to acquire nationality. After the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003, most of these Faili Kurds returned to Iraq since its new Nationality Law of 2006 contained a provision that allowed them to reacquire Iraqi nationality. However, many have not been able to benefit from this, as reacquiring nationality is complicated and burdensome.

Besides the Faili Kurds, groups from the Dom community, a nomadic Romani people originally from the Indian subcontinent, were denied nationality. The Dom have lived in Iraq for centuries, all the while maintaining their historic culture and language. As a result, many have never integrated into formal Iraqi structures, nor have they benefi ted from any kind of state protection. Stigmatized and marginalized, generations have lived without any form of documentation, including Iraqi nationality.

their citizenship or regained it, especially

in the border regions of Iraq? No one knows

Other displaced communities that are stateless, or at risk of statelessness, are refugee populations living in Iraq – most notably Palestinians and Syrians. There are over 8,000 Palestinian refugees registered with UNHCR in Iraq; the true figure is probably higher. According to the 2006 Nationality Law and the Protocol for the Treatment of Palestinians in Arab States (the Casablanca Protocol), Palestinian refugees are excluded from naturalization and are therefore left stateless. In addition, there are over 250,000 Syrian refugees in Iraq, mostly residing in the Kurdistan Region. An unknown number of them are stateless Syrian Kurds who lack a nationality or cannot substantiate their link to Syria. Syria’s Nationality Law discriminates against women transferring their nationality to their children, and Iraqi civil registration procedures are complicated. As a result, many children of Syrian refugees lack registration.

The challenges facing stateless people in Iraq are manifold. Two big problems are that the very status of “stateless” is not recognized, and that it is hereditary. Iraq does not have safeguards for children born without nationality. Displacement that lasts over generations exacerbates families’ struggles to obtain documents. The solution must include resolving the cases of displacement, ending discrimination against communities, ending gender discrimination under the law, and harmonizing and simplifying access to civil registration for everyone in the country, regardless of their status.

This contribution is licensed under the following copyright licence: CC-BY 4.0

The article was published in the Atlas of the Stateless in English, French, and German.