Share Twitter Facebook Email Copy URL

As sea levels rise and deserts spread, more and more people are being displaced. Refugees dislodged by climate change risk becoming stateless. Legal frameworks for states with no habitable land must be in place ahead of time.

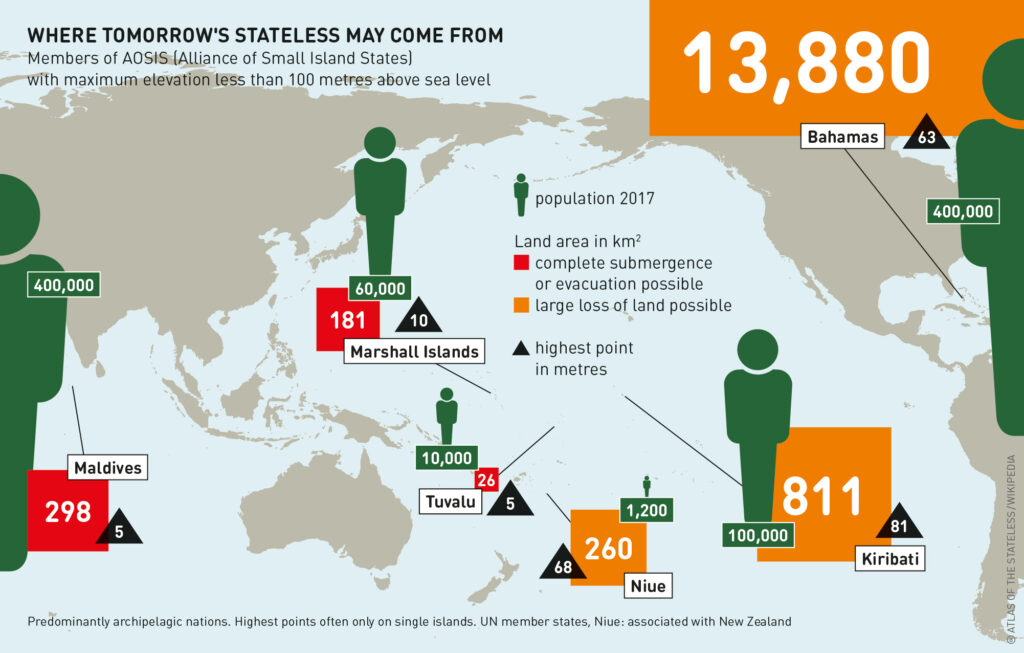

Rising sea levels are making it impossible to live in some coastal areas. The land is being inundated – or it is saturated with water for such long periods that buildings become uninhabitable and crops die from water logging or salinity. Low-lying island states such as Kiribati, Tuvalu and the Marshall Islands are being flooded and may disappear altogether beneath the sea. At the other end of the spectrum, parts of Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia and Sudan are becoming too dry to sustain habitation. As climate change displaces people, it also erases their cultures, histories and knowledge. It threatens the very existence of their states.

For a state to exist it must fulfill four requirements under international law: it must have a permanent population, have a government, be independent, and have land. Current international legal and political systems envisage the dissolution of a state only through conquest, succession or amalgamation. There is no provision for a state that faces extinction as a result of climate change. It is therefore important to examine what would happen to states that fail to meet one or more of the four requirements above.

The land question is the most pressing. The Montevideo Convention, which lays down the territory requirement for statehood, states in Article 1 only that the territory must be defined – not that it needs to be permanently habitable. Nor is there a requirement for the population to reside in this specific territory. The land requirement should therefore be ignored in favour of a more relevant assessment – the state’s ability to manage the needs and affairs of its population, many of whom will have been displaced.

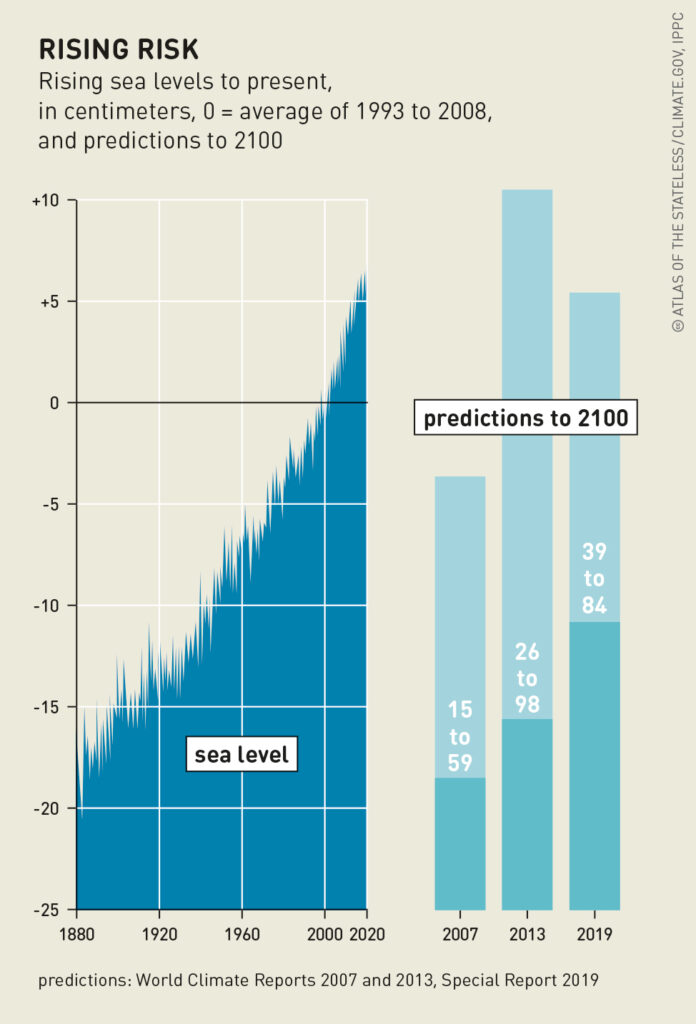

predictions about the rise in sea level by 2100 –

and the forecasts are increasingly alarming

Can a government serve a dispersed population? Climate change will force many people to migrate well before any state disappears, either politically, through desertification, or beneath the waves. Many inhabitants may insist on remaining in their homeland, but many others will be forced to move if their land becomes uninhabitable.

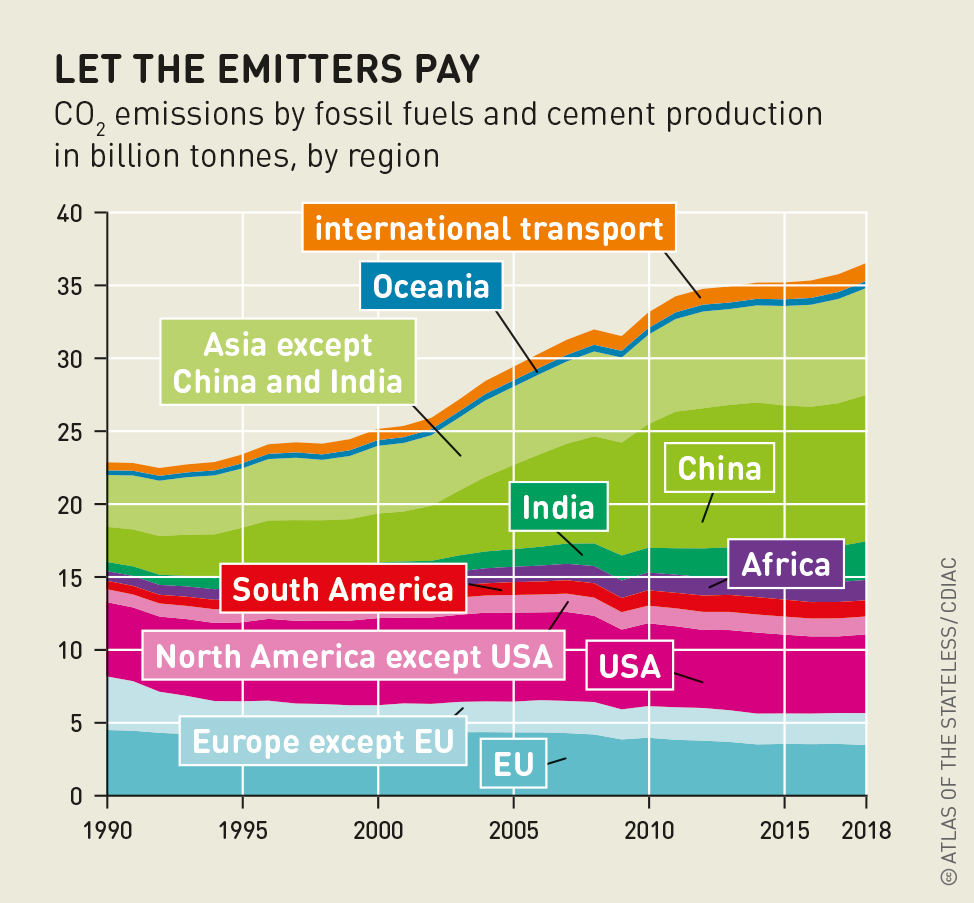

Those states whose sovereignty and survival are currently threatened have contributed only a tiny fraction of the global emissions that have caused the climate crisis. They are not to blame. The international community must acknowledge this and respond accordingly.

along with changing currents and stronger storms,

are threatening island and coastal states

Measuring how much individual states are to blame for their contributions to global emissions is difficult. Besides, states are unlikely to accept any such liability. From a legal perspective, the bulk of global emissions before 1990 did not violate any law: no legal standards for emissions yet existed. But taking 1990 as the point when the impacts and dangers of climate change became reasonably foreseeable, then any failure by polluting states to prevent harm caused to other states and the global commons is a clear violation of international law. The so-called “no harm rule” is a widely recognized principle of customary international law: a state is duty-bound to prevent, reduce and control the risk of environmental harm to other states. Looking forward, the international community has an undeniable duty to act.

What happens if a state become uninhabitable and its population has fled? The government may be unable to manage a flooded or desertified territory and serve the displaced population. The displaced people are unlikely to qualify as refugees under the legal definition: they are not fleeing violence or persecution. Nor would they qualify as stateless if their home state still legally exists, even if it has no effective government or habitable land. It is therefore important that governments can continue to serve a displaced population to prevent the creation of a new category: people who are “effectively stateless”.

for the oceans have been publicly known.

It is easy to see who is responsible

A migration crisis can be avoided if frameworks are in place ahead of time. Populations displaced by the climate crisis will need to be accommodated semi-permanently by host states. The home and host governments shall have to agree on the rights of the displaced population. The effective extinguishment of states must be avoided to prevent new stateless populations being created by the climate crisis.

Cities in wealthy countries are preparing for higher sea levels. New York City, for example, is planning high-water barriers on Manhattan Island. Poorer countries cannot afford similar defences. It is a collective duty to make provisions for the future, and to ensure that the vulnerable who will be displaced through the climate crisis do not also become stateless.

This contribution is licensed under the following copyright licence: CC-BY 4.0

The article was published in the Atlas of the Stateless in English, French, and German.