Share Twitter Facebook Email Copy URL

The end of colonialism led to the independence of many countries and a new nationality for many of their inhabitants. But not all. Some people were left stranded: immigrants in the newly independent countries had no state that would accept them. That is the case of the Karana, a minority group in Madagascar.

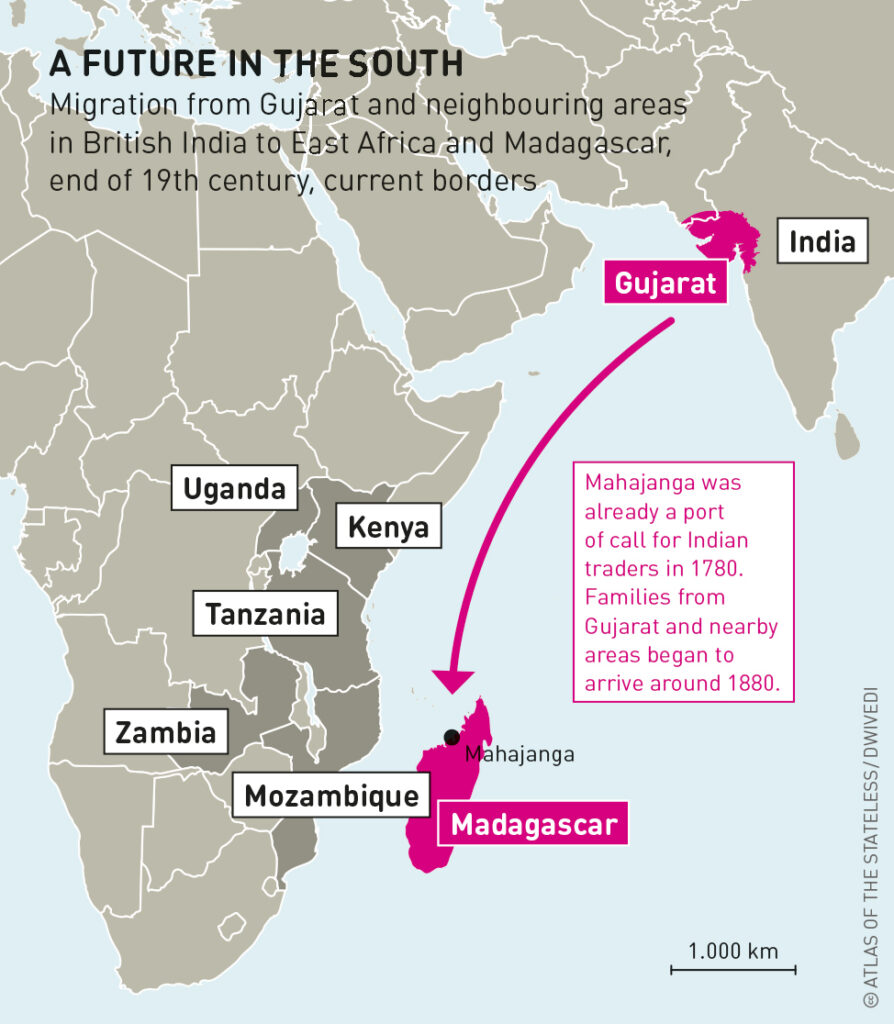

In Madagascar, people of South Asian origin are known as “Karana”. Most of them trace their ancestry to the Kathiawar Peninsula in Gujarat, which they left long before India and Pakistan gained their independence in 1947. The largest wave of migration occurred in the second half of the nineteenth century. In 1999 their population was 20,000; today it is an estimated 25,000.

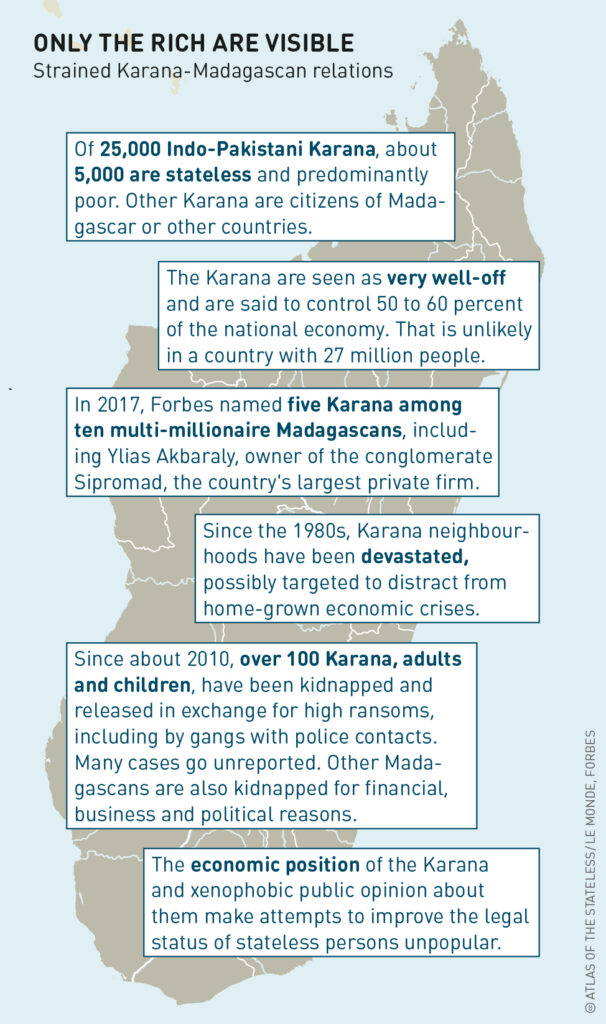

The term “Karana” derives from the word Koran, or Qur’an, since the majority of the Karana people are Muslim. The Karana are divided into five nationalities: Indian, Pakistani, French, British, and Malagasy. But approximately 5,000 are stateless, according to Karana community leaders and studies by Focus Development Association on behalf of UNHCR.

nationality status, many of the poor did not

manage to be naturalized by colonial France

Madagascar’s Nationality Code, drafted after independence in 1960, established Malagasy nationality as determined by “filiation” – the legal relationship between parents and children. Hence, a Malagasy blood relationship was required for Malagasy nationality. According to René Bilbao, a Malagasy magistrate, the purpose of the code was to exclude persons of European and Asian ethnicity from Malagasy nationhood.

As a result, Karana people born on Malagasy territory prior to 1960 were not able to keep their Indian nationality unless they could prove their distant Indian ancestry. In addition, the Indian Citizenship Act stipulated that residence outside India for seven years would lead to the loss of Indian nationality. Nor could they become French citizens because the nationality law in the French colonies and subsequently in the overseas territories was complex. Before 1908, nationality was transmitted according to the right of blood; after 1908 by birthright. But decrees in 1933 and 1953 abolished birthright citizenship (jus solis). As a result, it was difficult for South Asian immigrants to acquire the French nationality. Between 1935 and 1949, fewer than 15 “French subjects” a year were naturalized as French in France’s West African territories. Many immigrants to Madagascar remained without nationality, and statelessness was transmitted from generation to generation.

efforts to find a solution for a relatively

small group of stateless persons

Today, naturalization is entirely at the discretion of the Madagascar government. Paradoxically, naturalization is even less accessible for stateless Karana persons than for foreigners who came to Madagascar later. The Malagasy state’s fear of giving citizenship to the Karana stems mainly from the fact that doing so would allow them to buy land, something only granted to nationals. This is a very sensitive issue because the Malagasy are very attached to the land, which they regard as the land of their ancestors, and so to land ownership. Since other economic and social factors also play a role, even naturalized Karana cannot occupy higher political offices or positions.

Without a reform of the Nationality Code, the issue of statelessness of the Karana people cannot be resolved. Unlike the Chinese, who have integrated more easily, the Karana people are considered unassimilable. Their marriages tend to be endogenous and take place between members of the same religious group, and often the same caste.

Although they speak Malagasy, the Karana have retained their own language, traditions, way of life and customs. The wealth of a few Karana people gives rise to feelings of rejection, mistrust and sometimes hatred towards the larger Karana community. Some Karana families are indeed wealthy and control swathes of the Malagasy economy: real estate, banking, energy, cars and industrial equipment. This sparks xenophobic protests, sporadic riots and the looting, and burning of their property – known as OPKs (opérations karanas). More recently, the Karana have been the preferred target of kidnappings.

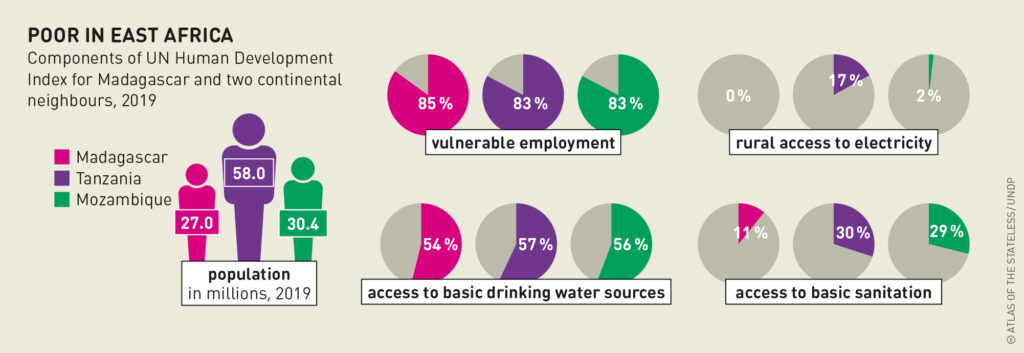

The stateless Karana, however, are generally poor and have neither the money nor the influence to acquire documentation. Stateless Karana are considered foreigners in Madagascar: they must regularly renew their visas and are required to obtain residence permits. With the introduction of biometric identification, the fees for documents have become prohibitive for people with low incomes. Renewing a residence permit has become psychologically and financially exhausting, and may be a humiliating experience. Many Karana therefore live in illegality, without papers, and so lack fundamental rights to decent formal employment, education, training, medical care and travel.

to guarantee basic services

for large sections of the population

Officially, Karana people have no status in Madagascar. The Stateless Persons Office, provided for by Decree No. 62-001, has still not been established – 58 years after independence. Despite UNHCR lobbying, Madagascar has not acceded to the UN Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness of 1961 or the UN Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons of 1954, and there is no indication that it intends to do so.

Nevertheless, the authorities are increasingly aware of the issue of statelessness. In December 2019, Senator Mourad Abdirassoul presented a bill to modify provisions of the Nationality Code in order to resolve statelessness by 2024. This bill is currently under consideration.

This contribution is licensed under the following copyright licence: CC-BY 4.0

The article was published in the Atlas of the Stateless in English, French, and German.