Share Twitter Facebook Email Copy URL

One sequence of historical wrongs – antisemitism in Europe, culminating in the horrors of the Holocaust – led to the creation of Israel. But that gave birth to another set of wrongs: the displacement of Palestinians from their homes and their homeland. The Palestinian diaspora still has no hope of return, and many are still not accepted in the places where they live.

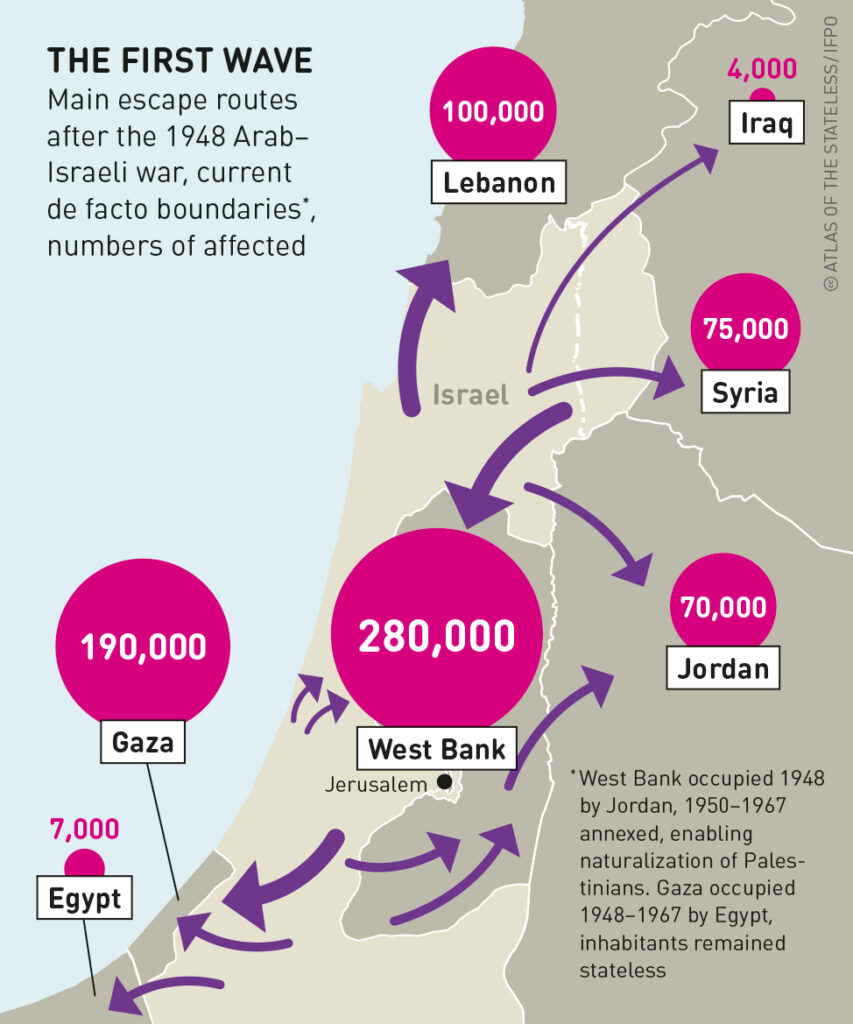

Large numbers of Palestinians were forced out of their homes when the state of Israel was created during the first Arab–Israeli war in 1948. While the founding of Israel provided a Jewish homeland for victimized Jews in Europe, much of the Palestinian population was dispersed from its homeland – in what Robin Cohen of the University of Oxford calls a “victim diaspora”.

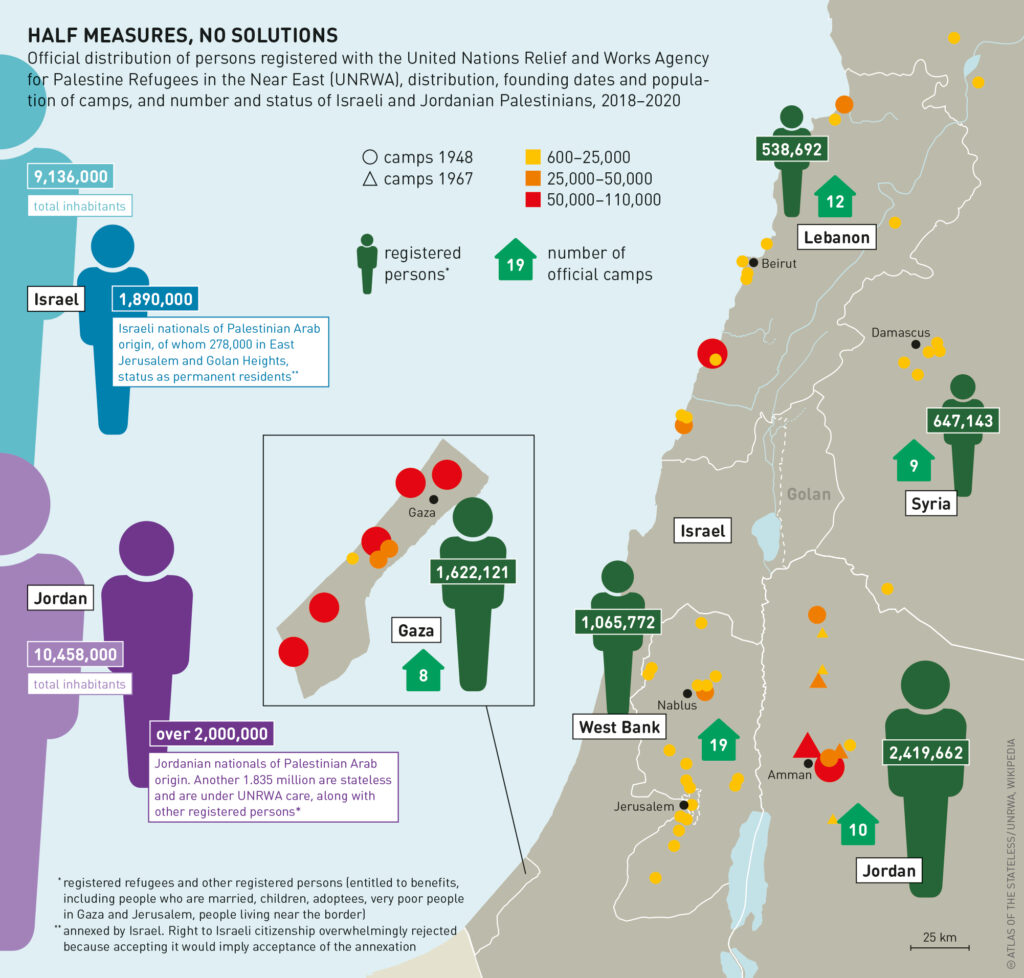

The number of Palestinians originally displaced from Mandatory Palestine is unclear: estimates range from 726,000 (according to the United Nations) to 810,000 (the British government). Since then, their number has grown as a result of natural increase and subsequent wars. By the end of 2018, roughly 8.7 million (66.7 percent) of the 13.05 million Palestinians worldwide counted as forcibly displaced persons: 6.7 million refugees from 1948 and their descendants (this includes the 5.5 million registered with the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East, UNRWA), plus another 1.24 million 1967 refugees and their descendants, 416,000 internally displaced Palestinians in Israel, and 345,000 internally displaced in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Together, they make up one of the largest and most protracted refugee cases in the world.

to flee. Many became stateless. Seventy years later,

they and their descendants are still stateless

The World Refugee Survey, issued by the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, designates protracted refugees as “camp refugees” or “warehoused refugees” who are often deprived of basic human rights in their countries of refuge. Palestinian refugees living in Arab host countries have different legal statuses and living conditions. While Palestinians in Jordan are granted full citizenship rights, those in Syria enjoy basic, but not full, citizenship rights. In Lebanon, Palestinians are deprived of most basic human rights, including their rights as refugees under international conventions. In Iraq, Kuwait, Libya and the Arab Gulf states, political vicissitudes determine the rights they are granted.

The Arab legal system for managing the Palestinian refugees’ situation consists of three instruments. Firstly, classification of the Palestinian refugees as stateless persons, regarding this as “positive discrimination”so as to prevent their permanent resettlement and preserve their right of return. Secondly, linkage between UNRWA’s mandate of continued assistance for the relief of the Palestine refugees to further conditions of peace and stability (UN Resolution 302 of 1949) and the implementation of a Conciliation Commission to facilitate peace between Israel and Arab states (Resolution 194 of 1948). Thirdly, measures and standards adopted by the Arab League to ensure temporary protection of the Palestinian refugees, most importantly the Casablanca Protocol of 1965 – an instrument that has never been fully implemented.

Some host countries, such as Lebanon, do

not want the option of naturalization

The majority of the Arab states, and especially Lebanon, have discriminated against Palestinian refugees because of fears that they would de facto be resettled permanently in their territories. But outside the region, Palestinian communities are not always included in measures to protect the stateless. This is partly because their unique situation is not acknowledged, and partly because some countries recognize the state of Palestine while others do not. Even with regard to international protection, Palestinians are distinct from other refugees under the mandate of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. The UN Conciliation Commission for Palestine was created to find a solution to the Palestinian refugee problem and to safeguard their right to return. But it failed to carry out its mandate, and by the early 1950s its operations were restricted to property identification and documentation and it was wound down. Since then, the UNRWA has delivered “relief protection” in the form of education, health and social services. But this does not meet generally applicable standards for the support of refugees.

The absence of adequate protection for Palestinian refugees by most of Arab states, the collapse of protection by the Conciliation Commission, and the limited protection provided by UNRWA have led to severe gaps in the international protection of Palestinian refugees. The Palestine Citizenship Order 1925–41, which regulated the Palestinian citizenship in Mandatory Palestine, terminated with the end of the British mandate and the proclamation of the state of Israel in 1948. The Nationality Law (5712/1952) established in Israel in 1952, imposed a new set of rules. Given the deadlock that the Oslo peace process has reached and the erosion of the two-state solution, legal experts and international law scholars argue that the current Palestinian “entity” does not fully satisfy the international criteria of statehood according to the Montevideo Agreement: a permanent population, a defined territory, government and the capacity to enter into relations with other states. If no state exists, the Palestinian nationality does not exist, and Palestinians who have not acquired the nationality of a third state continue to be legally stateless.

This contribution is licensed under the following copyright licence: CC-BY 4.0

The article was published in the Atlas of the Stateless in English, French, and German.