Share Twitter Facebook Email Copy URL

Most people live in one place: they have a house or a flat, perhaps even a garden. Groups with a mobile lifestyle do not fit in, and thus are viewed with suspicion and hostility. That is true of the Roma in Europe, even though many have been settled for generations. The possession or acquisition of documents proving citizenship is a major problem.

Rom” means “man” in the language of the Roma (or Romani or Romany) people. “Roma” is used as an umbrella term to cover a range of European groups and subgroups, including the Roma, Sinti, Manouche, Calé, Kale, Romanichal, and many others. Linguistic research indicates that the Roma originated in India and arrived in Europe in the Middle Ages. With an estimated 10–12 million people, the Roma are by far the largest ethnic minority in Europe.

They still experience difficulties in applying for a residence permit or citizenship. Majority societies have always tended to reject them. Repressive measures have ranged from forced assimilation and restriction of rights to persecution – culminating in genocide by the Nazis in the Second World War, in which some 500,000 Roma were murdered.

Even today, the groups often referred to as “Gypsies” are ascribed characteristics that stigmatize them as deviating from the norms of society. Racism against Roma, known as “antiziganism” or “antigypsyism”, is expressed in the form of violence, hate speech, exploitation and structural discrimination. Like antisemitism, it is based on an ideology of racial superiority, a form of dehumanization and of institutional racism, nurtured by discrimination throughout history.

This is especially the case in the Balkans, home to a large percentage of the European Roma. With the disappearance of the socialist governments of Eastern and Southeastern Europe, the situation of the Roma, which was already difficult, worsened dramatically. Under socialism, the Roma were subjected to the destruction of informal settlements, resettlement and expulsion. But now the relative normalization of nationalistic and racist ideologies in some places has led to greater discrimination in the labour market, education and healthcare systems. Poverty and a lack of documentation mean that more than half of the Roma living in segregated settlements are often forced to endure inhumane conditions.

level of mobility as the cultures that surround them. The

idea that they are wanderers is a persistent myth

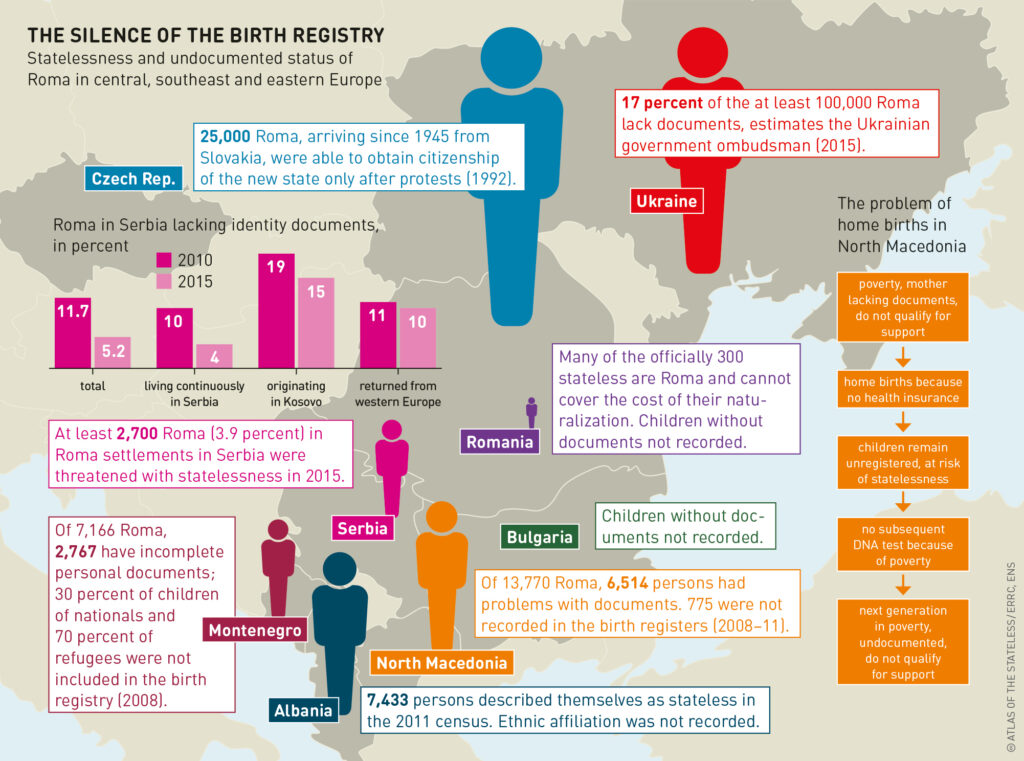

In Yugoslavia, many Roma moved frequently and did not appear in birth registers or residence records. When Yugoslavia broke up into its component parts, many lost their citizenship. The same happened to the Roma living in Western Europe: they became de facto stateless and still experience problems with their residence status or when applying for a new citizenship. This is in part due to the fact that the authorities do not provide assistance in obtaining the necessary documents.

As a minority subject to discrimination, Roma from Yugoslavia were especially vulnerable to the social upheavals and wars in the region. Those who were able to flee the war in Bosnia in 1992–95 lost both their homes and their citizenship. Roma were also collateral victims during the armed conflicts in Kosovo in 1998–99. More than 100,000 Roma, Ashkali and Balkan Egyptians were forced to flee. Some 50,000 sought asylum in the European Union, but in Germany, for example, they were only granted a “tolerated” status.

a vicious circle that can pass

from one generation to the next

Some years after the war, Germany and other European countries negotiated repatriation agreements with the Balkan states to return people without a permanent residence status in the European Union to their countries of origin. As a result, several tens of thousands of Roma were deported to Serbia, Kosovo and North Macedonia. The majority tried to return to Germany and reapply for asylum.

This was possible until 2014 and 2015, when Germany and other countries in the EU added the Balkan states to the list of safe countries of origin. According to refugee organizations, the introduction of this list of “safe countries” led to the erosion of legal protections for asylum-seekers. For the Roma, this made it virtually impossible for them to obtain asylum in the EU. This also made it easier to deport Roma who were living in the EU. In 2015, a total of 21,000 people were deported from Germany alone, three-quarters of them to the countries of the Western Balkans.

In the Balkan countries, deported Roma often only have refugee status; many have no valid identity documents, or their documents are incomplete. As a result, they can only find accommodation in poor, informal settlements, which in turn means that they do not have a valid address they can use to register as residents. There are various programmes for their integration and inclusion, such as the 2011 EU Framework for National Roma Integration Strategies, which is in effect until 2020. However, they have not led to a significant improvement in situation of the Roma in the Balkans. On the contrary: the rise of right-wing extremism in Europe and the accompanying spread of hatred towards refugees and Muslims means that Roma throughout Europe are now living in fear again.

This contribution is licensed under the following copyright licence: CC-BY 4.0

The article was published in the Atlas of the Stateless in English, French, and German.