Share Twitter Facebook Email Copy URL

South Africa has one of the most enlightened and liberal constitutions in the world. But even here, thousands of people fall into, or are born into, the limbo of statelessness. Loopholes in laws leave gaps – gaps that large numbers of people can fall through. Children are especially at risk.

Estimates suggest that there are about 10,000 stateless people in South Africa – however, no reliable statistics exist. Among the reasons for statelessness are the administrative and legal hurdles that make it difficult to register a birth. Section 28 of South Africa’s Constitution states that every child born within South Africa’s borders has the right from birth to a name and a nationality, and should be issued a birth certificate. The country has signed a slew of international agreements. The South African Birth and Death Registration Act (No. 51 of 1992) and the associated Regulations (issued in 2014) govern the issuance of birth certificates and the process and documents required to register a birth.

Despite these regulations, children born in South Africa to foreign nationals do not automatically acquire South African citizenship. The Act requires that foreign parents first produce a valid visa or asylum or refugee permit. But for asylum seekers and refugees, obtaining such documents is fraught with barriers, expenses and delays. People may become undocumented for various reasons: their residence permit has expired, they have not been able to renew their visa outside the country, refugee offices are closed, or immigration laws are restrictive. Births must be registered before the baby is 30 days old. Otherwise, the parents must apply for a late birth registration – a process that is lengthy and onerous, as asylum or refugee documents must be verified.

Foreign nationals who have obtained a birth certificate may continue to face obstacles. The certificates for foreign nationals are handwritten – the birth is not entered into the population register. As the Department of Home Affairs does not reissue handwritten birth certificates, parents who have lost a certificate cannot get it reissued. Their children are denied proof of their nationality. Until recently, a father of a child born out of wedlock was not allowed to register the birth without the mother being present. This changed in July 2018, following a ruling by the Grahamstown High Court stating that the relevant regulation was unconstitutional.

Some separated or unaccompanied foreign minors do not hold legal status and are at risk of statelessness because of restrictive immigration laws. According to the law, first-time visa applications must be made in the country of origin, which is obviously not possible for children who are already within the country. As there is no visa category for unaccompanied children and young people, they cannot be recognized as asylum seekers or refugees.

left by their parents, abandoned in extreme poverty,

taken in after abuse, or fleeing from a war zone

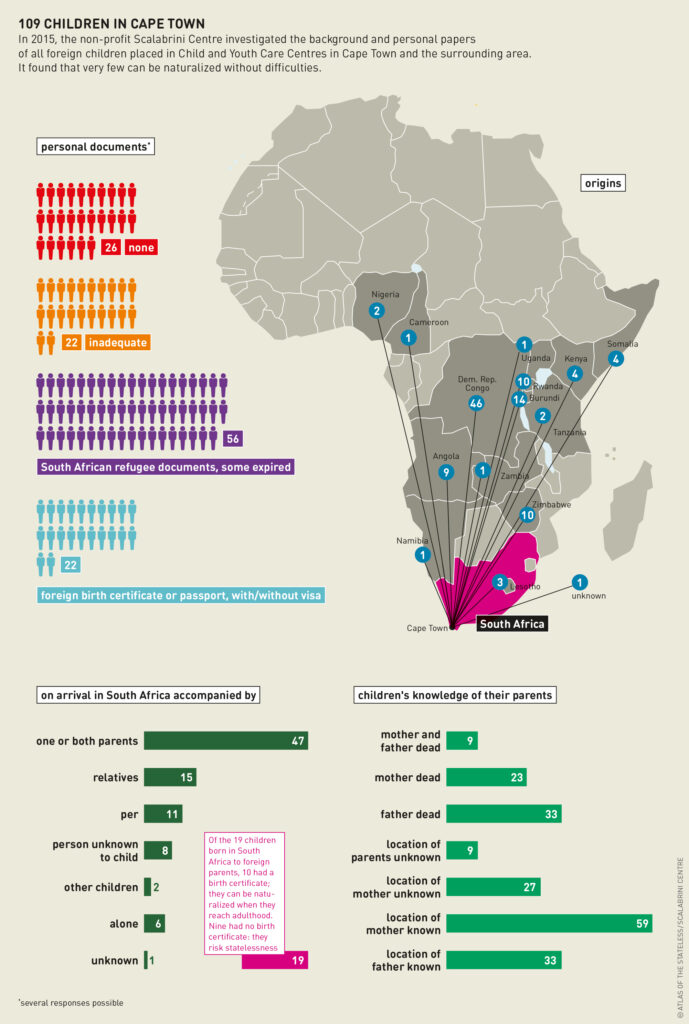

A survey by the Scalabrini Centre of Cape Town in 2015 found that 80 percent of the foreign children in child and youth care centres had no birth certificates or documents which would enable them to claim a nationality. Because of irregular migration, a lack of birth certificates, passports or other documentation, and lost contact with their families, an estimated 15 percent of the children were at some risk of statelessness. Another study in 2017 on unaccompanied and separated foreign children in the Western Cape found that 55 percent of the surveyed children did not possess birth certificates; 21 percent were at risk of statelessness.

Section 4(3) of the South African Citizenship Act, as amended in 2010, permits foreign children born in South Africa to be granted citizenship when they reach adulthood. But this applies only to children born after January 2013 and for whom births have been registered – which means their parents must have held valid documents. The interpretation of this provision is subject to litigation. Section 2(2) of the same Act provides for the citizenship for those individuals born in South Africa who are not recognized as citizens of any other country. However, these individuals must hold a birth certificate. So section 2(2) appears to be of little help to stateless individuals.

South Africa can reduce the risk of statelessness for children in various ways. It should grant nationality to all children at risk of statelessness. It should review all relevant laws, including those covering birth registration and citizenship, and amend and remove discriminatory sections that inhibit the rights of the child to a nationality. It should systematically identify all undocumented children living in child and youth care centres and make sure they get a birth certificate and a nationality. It should strengthen data collection on refugee children, and streamline their registration and documentation. It should ensure that the Refugees Act is in line with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, and it should consider allowing unaccompanied children to settle permanently.

This contribution is licensed under the following copyright licence: CC-BY 4.0

The article was published in the Atlas of the Stateless in English, French, and German.