Share Twitter Facebook Email Copy URL

Statelessness is all too often invisible. Not recognised as nationals of any country, stateless people are often deprived of basic rights. The IBelong campaign, led by UNHCR, is trying to change this by raising awareness about the issue and pushing for change — with some initial successes.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is best known for its work with refugees. It is also the UN agency mandated to protect stateless people and seek solutions to their plight. In 2014, it launched an ambitious campaign to end statelessness by 2024, also known as the IBelong Campaign, or, with a hashtag, as the #IBelong Campaign. Now halfway through its 10-year life span, this campaign has boosted awareness of statelessness and galvanized momentum in places where the phenomenon of people living without any nationality – and indeed the word “statelessness” itself – were previously not acknowledged.

This is particularly true of Africa, but there has been notable progress on other continents as well. Media coverage of the issue tends to be dominated by the worsening of the situation of certain stateless populations, such as the Rohingya in Myanmar, or the risk of new problems, notably in India. Despite this, the quiet but important positive steps undertaken by dozens of countries deserve recognition. Various countries pledged concrete action to address statelessness by 2024 at a high-level event convened by UNHCR in 2019. These promise significant progress to reduce and prevent statelessness in the years ahead.

To appreciate recent achievements in the fight against statelessness, it is important to understand the origins of the problem. One major cause is state succession, i.e., when one state ceases to exist and its successors do not recognize certain residents as their citizens. Apart from state succession, the drivers of statelessness include the presence of outright discrimination (on the basis of ethnicity, race, or religion, for example) in nationality laws combined with the absence of safeguards against statelessness in those same laws.

People may also be left stateless when nationality laws are based on a strict interpretation of jus sanguinis (citizenship by descent). People who are descendants of forebears who migrated generations ago may have lost ties to their countries of origin without being recognized as belonging to their country of birth. Poor civil-documentation practices, particularly where many births are not registered or certified, can also lead to statelessness, especially for members of minorities. Birth certificates record a person’s place of birth and parentage – the two key factors that are relevant for a person’s claim to citizenship. People who lack proof of entitlement to citizenship often face problems if they do not look like the dominant group, speak its language or follow its religion.

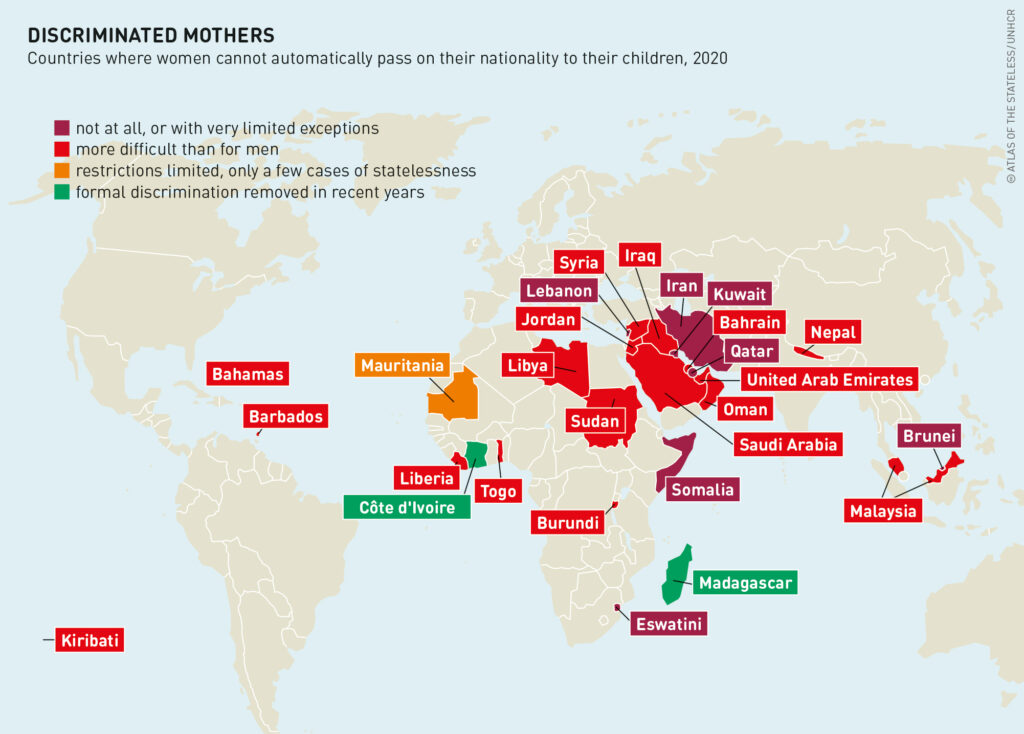

Reforms to nationality laws and improved civil registration practices can prevent statelessness from occurring in the first place. In both areas there is some cause for optimism. Since the start of the IBelong Campaign, seven countries (Armenia, Cuba, Estonia, Iceland, Latvia, Luxembourg and Tajikistan) have introduced legal provisions to grant nationality to children born in their territory who would otherwise be stateless. Two (Cuba and Paraguay) have introduced provisions to grant nationality to children born to nationals abroad who would otherwise be stateless. Another two (Madagascar and Sierra Leone) have reformed their nationality laws to allow women to confer their nationality to their children on an equal basis with men.

world are still prevented from passing

on their citizenship to their children

Some 25 states around the world still do not allow mothers the unfettered and equal right to confer nationality to their children. But there is momentum towards reform in several of them. This is largely thanks to the engagement of civil society, including many grassroots organizations and the Global Campaign for Equal Nationality Rights, a network of NGOs and United Nations agencies. Legal reforms will also be spurred as states finally sign up to the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness. This treaty lay largely dormant for many years; as recently as 1990, it had been ratified by a mere 15 states. But by 2020, 75 states had done so. Since the IBelong Campaign was launched, 14 states – Angola, Argentina, Belize, Burkina Faso, Chile, Guinea-Bissau, Haiti, Italy, Luxembourg, Mali, North Macedonia, Sierra Leone, Peru and Spain – have all ratified the Convention.

In addition to positive legal reforms, birth registration rates have continued to rise globally. Innovations in technology and best practices, such as direct hospital notification of births to civil registries, have aided coverage. Rates remain lowest in the least developed countries, where the absence of birth registration makes it hard for individuals to obtain the identity documents they need for education, legal employment and access to services. In adopting the Sustainable Development Agenda in 2015, all member states of the United Nations recognized that birth registration and documentation of legal identity are development issues. Through Sustainable Development Goal 16.9, they undertook to provide “legal identity for all, including birth registration, by 2030”.

In addition to movement on the prevention side, there has been an increase in the political willingness of many states to resolve statelessness on their territories. This has been most evident in Central Asia, where statelessness caused by the breakup of the Soviet Union has lingered for decades:

- In 2019, Kyrgyzstan became the first state worldwide to declare a resolution of all known cases of statelessness on its territory. The 2019 Nansen Award recognized the legal aid work of the organization led by lawyer Azizbek Ashurov. This was the first time this prestigious prize has been given for efforts to address statelessness.

- In 2020, Uzbekistan adopted a new law that will confer citizenship immediately upon approximately half of its stateless population, an estimated 50,000 people, and help address the situation of others.

- In 2020, Tajikistan adopted an amnesty law to allow undocumented persons to obtain identity documentation and put them on a path towards naturalization.

Important measures to reduce statelessness have been taken in Africa:

- Kenya has provided nationality to the formerly stateless Makonde minority, making them the country’s 43rd official tribe. It has promised to provide nationality to the Shona, another minority group, and has set up a national task force with the goal of eradicating statelessness.

- Cote d’Ivoire, which has the highest known number of stateless persons in Africa, has adopted a national action plan to end statelessness. It has taken measures to ensure that foundlings, including older war orphans, will acquire Ivorian nationality.

- Many African states pledged in 2019 to undertake studies of statelessness, adopt national action plans, and accede to the 1954 Convention on the Status of Stateless Persons or the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, or to both treaties.

- Liberia and Eswatini, two of the remaining 25 states that do not allow mothers to confer their nationality to their children on an equal basis as fathers, have promised to address this before the end of the IBelong Campaign.

Progress has also been made in the Asia Pacific region:

- Thailand, which has one of the highest known number of stateless persons in Asia at just over 400,000 (famously including some of the boys dramatically rescued from the Tham Luang cave in 2018), is taking bold steps to confer nationality on those without it. The government has made a political commitment to try to fully resolve statelessness by 2024.

- Malaysia’s government recently adopted a five-year plan to resolve statelessness among its population of Tamil origin.

- The Philippines and Indonesia are cooperating with each other to address cases of persons who have ties to both countries but have no proof of citizenship to either.

In Europe, almost all countries are now party to the statelessness conventions. The numbers of stateless persons in the Baltic states, the highest in Europe, are on a decline, thanks in part to reforms by Estonia and Latvia to ensure that children born to persons without nationality automatically acquire their nationality at birth. Since the start of the IBelong Campaign, many states in the Americas, including Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Panama, and Uruguay, have adopted procedures to determine statelessness. These are similar to asylum procedures for refugees, but focus on identifying and conferring a protected status on stateless persons pending their naturalization. Colombia has decided to confer citizenship on all children born there during a certain period to parents who have fled from Venezuela. This is a welcome development that benefits tens of thousands of newborns who would otherwise have been left in legal limbo. They were unable to obtain Venezuelan documentation and were technically not eligible for Colombian citizenship.

While these are significant positive developments as compared with the situation before 2014, persistent challenges remain, and new ones continually arise. These include the threat of new situations of statelessness posed by increased forced displacement and the rise of ethno-nationalism in places like India. The use of deprivation of nationality as a counter-terrorism measure is another cause of concern. Such measures may be abused as a tool to pursue political opponents or others out of favour with those in power. Hope lies in the increased awareness of the statelessness issue, coupled with generally higher levels of political will.

Mainstream civil society also increasingly recognizes that statelessness is an important issue in securing women’s, minorities’, and children’s rights. The 2015 special report by UNHCR, “I am here, IBelong: The urgent need to end childhood statelessness”, stimulated a coalition of NGOs, UNICEF and UNHCR known as Every Child’s Right to a Nationality. This coalition is active in 20 states and growing.

A 2017 UNHCR report, “This is our home: Stateless minorities and their search for citizenship”, led to increased interest by many, including the Minority Rights Group and the UN Special Rapporteur on Minority Issues. In 2018, statelessness was a focus of the UN Forum on Minority Issues for the first time. These developments are encouraging. Statelessness is on a spectrum with other dangerous forms of exclusion. The fight for citizenship rights for all is an important part of the fight for inclusive and open societies.

This contribution is licensed under the following copyright licence: CC-BY 4.0

The article was published in the Atlas of the Stateless in English, French, and German.