Share Twitter Facebook Email Copy URL

Still a diamond in the rough?

Comment by Tetet Lauron, in cooperation with Nadja Charaby and Katja Voigt.

“The UN was not created to take mankind into paradise, but rather, to save humanity from hell.”

– Dag Hammarskjold, UN Secretary General 1953-1961.

This year marks the seventy-fifth anniversary of the United Nations, the institutional bedrock of the post-war international order established to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, and promote social progress, better living standards and human rights. This should be a very good moment for the UN to go through an existential rethink of its core values and determine whether it needs a “system reboot” to remain relevant and essential to meeting current and future challenges.

It is ironic that the world today is at odds with the very ideals on which the UN was founded. Wars and conflicts are causing unprecedented humanitarian crises, worsened by rising intolerance and xenophobia. The world is far from resolving socio-economic problems, and although universal recognition of human rights and fundamental freedoms has been nominally achieved, current authoritarian and neoliberal tendencies undermine these rights and whatever progress has been made in the fight against hunger, poverty and inequality.

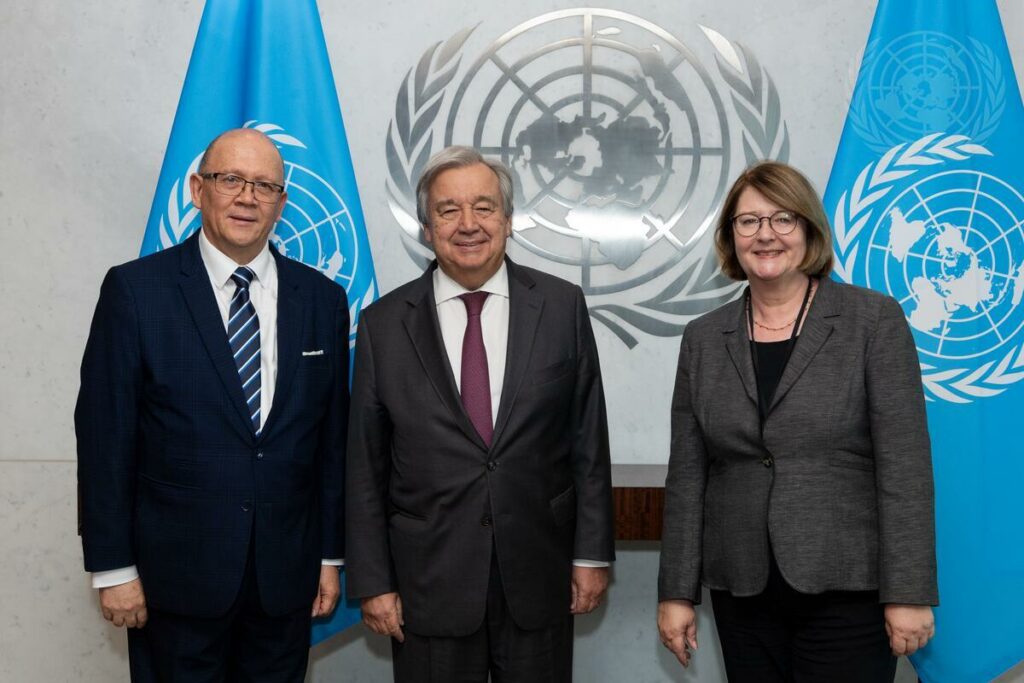

The COVID-19 pandemic—spreading human suffering, infecting the global economy, and upending people’s lives on such a scale that the likelihood of a global recession of record dimensions is a near certainty—is unlike anything in the UN’s 75-year history. As UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres stated at the opening of the General Debate of the 2019 United Nations General Assembly, “multilateralism is under attack from many different directions precisely when we need it most.”

Aspirational Goals Ring Hollow against Systemic Barriers

It has been five years since the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) or the “2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” were adopted by all UN member-states in August 2015 as a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity by 2030. The SDGs coincided with other intergovernmental agreements reached in 2015, namely the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, the Addis Ababa Action Agenda on Financing for Development, and the Paris Climate Agreement. Annual reviews of the 17 goals, 169 targets, and 232 indicators at the High-Level Political Forum (HLPF) show that the SDGs are off track, prompting the UN Secretary General to call for more ambition, action, and resources to fast-track implementation. Mobilizing the necessary resources, estimated between 3.3–4.5 trillion US dollars per year in developing countries alone, is among the major challenges. Even as the final SDG negotiations were ongoing, governments were also deep in negotiations on a new global framework for financing sustainable development that would align all financial flows and policies with economic, social, and environmental priorities.

But beyond realizing “billions to trillions” for developmental goals lie systemic issues that civil society and other actors have raised time and again at both the UN and other forums. Agenda 2030’s implementation occurs in the context of multiple, interconnected crises, manifesting in ecological breakdown, the unrestricted power of multinational and transnational corporations, and perverse inequality. These are compounded by a number of alarming signs:

- The World Bank has warned that another financial crisis is in the offing with the general slowdown in the world economy and the rapid rise of global debt, which rose from 152 trillion US dollars in 2008 to 213 trillion by the end of 2017.

- The continued decline of Official Development Assistance (ODA) levels, totalling 153 billion US dollars in 2018, representing only 0.31 percent of the combined national incomes of developed countries, well below the agreed ratio of 0.7 percent ODA to gross national income. Apart from declining ODA levels, issues around the quality and quantity of aid remain, often criticized as serving the political and economic interests of donor countries rather than underdeveloped countries.

- The “corporatization of development”, whereby governments, in the mad drive to attract foreign investment, compromise their own sovereignty by relaxing prohibitions or granting concessions to foreign corporations. These measures include risk insurance and guarantees, public-private partnership (PPP) modalities, or allowing increased private investment in developing countries’ infrastructure. In its initial stages, PPPs were focused on economic infrastructure projects, but these ultimately expanded to include social sectors such as healthcare, water, housing, and education.

- The liberalization of the financial sector—that is, easing global regulations on financial transactions—dovetails with an increase in tax avoidance and evasion by corporations and billionaires. This aligns with the surge in illicit financial flows (IFFs), defined as “illegal movements of money or capital from one country to another, resulting in the loss of much-needed domestic resources to fund public initiatives or critical investments in public goods and services.”

- The decimation of developing countries’ domestic agriculture and manufacturing due to trade liberalization. The World Trade Organization (WTO) has become a place where corporations can sue governments for protecting certain sectors and industries in their national economies through the WTO’s Investor-State Dispute Settlement System (ISDS).

Developing countries face huge trade and balance of payments deficits, compelling them to resort to heavier borrowing and open up their economies even further, while rich countries protect their own. This has become a vicious cycle rooted in the dominance of the neoliberal agenda in the multilateral trade system. We must establish fair and equitable trade rules based on human rights, and systems must be in place to ensure fair wages, fair taxation, decent work conditions, and stronger environmental protection.

Growing inequality between and within countries is, according to an Oxfam report, due to the neoliberal economic system that enabled an explosion in the concentration of wealth and power to such an extent that 26 individuals possess the same amount of wealth as the world’s 3.8 billion poorest people.

Age-old inequalities on the basis of gender, caste, race, and religion—injustices in themselves—are exacerbated by the growing gap between the haves and have-nots. In order to be transformative and effective in “leaving no one behind”, sustainable development must do away with the neoliberal framework whose imperative of economic growth for private gain has systematically impoverished communities, worsened inequalities, and led to the breakdown of the earth’s natural systems.

Siloed Approaches and Policy Incoherence

Realizing the SDGs depends upon alignment and integration between national goals, strategies, and plans for implementation. But despite universality and indivisibility being guiding principles of the SDGs, its implementation is yet to achieve the desired integration, based on Voluntary National Reports (VNR) presented during the HLPFs that found member-states “cherry-picking” goals and targets to report their progress on. The fact that SDG implementation and reporting is voluntary and non-binding makes for a lack of genuine monitoring and accountability.

Member states are expected to showcase impact, progress and trends in their VNR presentations. However, the reporting that has taken place at the HLPF and regional spaces is not only devoid of any meaningful and genuine accountability because these are largely government self-assessment reports despite supposedly embracing an inclusive multi-stakeholder approach, but are also exercises where member states report achievements without having any critical perspective. Hardly any VNR report presents systemic reforms with transformative potential. At best, the VNRs are glossy presentations resembling tourism videos and fancy advertising campaigns for investments, grants, and aid money.

An Exclusive and Tokenistic Engagement Process

Unlike its predecessor, the Millennium Development Goals, the SDGs adopted a multi-stakeholder “whole of society” approach from the outset. Civil society, business, and other multi-stakeholder partnerships are intended to contribute to the achievement of the SDGs in implementation, reporting, and monitoring at national levels.

Governments take the lead in establishing a supposedly coherent national strategy to implement all SDGs, institutionalizing collaboration and coordination between government agencies and civil society. However, developing mechanisms for effective and meaningful stakeholder engagement beyond ad hoc measures remains challenging in many countries. It has been noted that there is a general lack of awareness of the Agenda 2030 four years into its implementation, even among subnational and local authorities.

Civil society is regarded an independent development actor taking on numerous roles as watchdogs, researchers, advocates, mobilizers, and more, including holding governments and other stakeholders accountable. But consistent with the trend towards shrinking spaces for civil society, engagement and policy influence particularly at the national level has been challenging and met with mixed results, especially as many governments regard engagement with civil society merely as a “box-ticking” exercise with which they must comply. This is in contrast to the red-carpet welcome that corporations get from the UN, governments, and other institutions that laud the private sector as the engine of growth and development.

Towards a “New Internationalism”

Multilateralism faces a crisis of relevance and legitimacy, triggered on the one hand by the rise of nationalist and populist political tendencies, and on the other by growing disillusionment among many over its failure to deliver real results that make a difference in people’s lives.

Because the UN has been deficient in delivering its mandate as the principal space where the international community comes together to set norms responding to the imperatives of development, there is a need to advocate for thoroughgoing reforms within the system for it to remain relevant and legitimate. With its unique convening power, the UN still offers the biggest stage in international diplomacy, although its global impact is fast diminishing. For multilateralism to remain meaningful, it must be reconceptualized and revitalize the United Nations.

A critical lens that evidences how and why the UN perpetuates the same neoliberal development framework—whose imperative of economic growth for private gain has systematically impoverished communities, worsened inequalities, and led to the breakdown of the earth’s natural systems—is paramount. What is also needed for effective critical engagement, however, is a contrasting positive vision, or what is termed as a “new internationalism”, focused on the implementation of global social rights, the democratization of international organizations, and the strengthening of multilateral action.

Global governance must enable a transformation of economic and social processes and structures to achieve development and environmental sustainability. A revitalized UN could play a crucial role in this shift, meaning that institutions, mechanisms, norms, and policies that shape global processes, arbitrate relations between actors, and provide a framework for cooperation in addressing global challenges must be reoriented if it is remain true to its mandate.

The UN observes its diamond year amidst an unprecedented situation in the world. How the multilateral system responds to a crisis of this magnitude will constitute an acid test in creativity, vision, leadership, and global solidarity. Only then will we know whether the UN is a diamond in the rough.