Share Twitter Facebook Email Copy URL

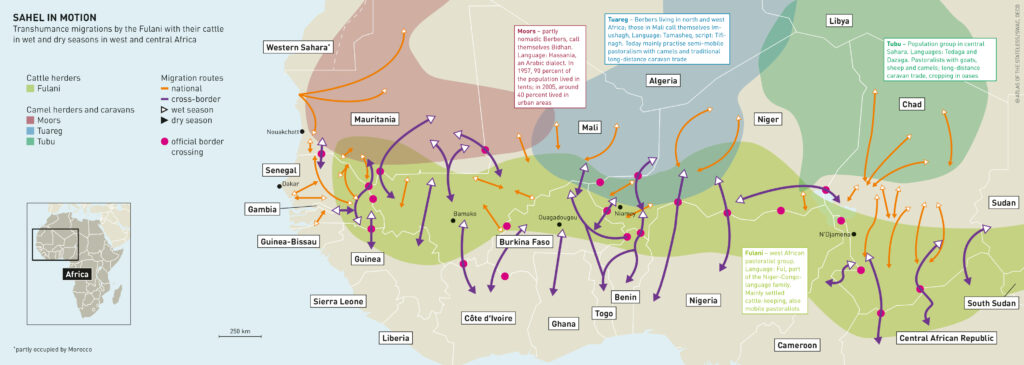

The concept of the modern state, and the rules of nationality, are based on the idea of residency within fixed boundaries. But millions of people, especially in the drier areas of Africa and Asia, move with their herds from place to place in search of water and pasture. Their lifestyle is far older than the boundaries that cut across their traditional grazing grounds.

Amongst those most at risk of statelessness are people belonging to ethnic groups that have traditionally followed a nomadic or pastoralist way of life – a population of many millions in Africa. Although many pastoralists are settled or semi-settled, or move only within one country, others have no fixed place of settlement and move across multiple borders with their livestock and belongings.

Nationality laws everywhere are poorly adapted to deal with the situation of those who have no fixed home. In most cases, to gain recognition of nationality a person must prove either their place of birth or descent from a person who has been resident in the country as of a certain date – in Africa, this is usually the date the nation regained its independence. There is a lack of national or international law relating to the determination of the nationality of those who are – or were – not “habitually resident” in any particular state.

In West Africa, the right to a nationality often depends on proving that two generations were born in the country. Yet very few births were registered during the colonial period, and registration rates still remain below 50 percent of all children in many states. A lack of birth registration may create problems for members of any community in establishing their nationality, but is less likely to be an obstacle for a child born to parents from an ethnic group that is known to be settled in the country.

The status of those who belong to nomadic communities, however, is always likely to be questioned. Members of the 25-million-strong Fulani ethnic group (known as Peul in French), traditionally cattle-herders with a pastoralist way of life, are found across West Africa and as far east as Sudan. They are often considered “foreign” in the states where they are present, especially where clashes over land use between agriculturalists and pastoralists prevail. At its most extreme, Fulani have been caught up in mass expulsions of alleged non-citizens. In 1982, Sierra Leone expelled Fulani who allegedly originated from Guinea. In 1988/89, Ghana expelled Fulani pastoralists, and did so again in 1999/2000. Of the 70,000 people driven out by the Mauritanian government in 1989/90 on the grounds that they were not citizens, the majority were cattle herders of Fulani ethnicity from the Senegal River Valley.

Even those Fulani who have lived for several generations in the same location, or migrate only within the borders of one country, may face resistance to the idea that they are nationals of that state, simply because they have a Fulani last name. Some victims of discrimination can obtain identity documents with the assistance of intermediaries who vouch for them (or by paying bribes). But the poorest and most marginalized may be unable to do so and remain unrecognized as nationals of any state. As a consequence, they are unable to access public services, including healthcare and education for their children, are excluded from the formal economy, and cannot exercise the right to vote or stand for public office.

borders in the Sahel hardly

match the nomadic

economy, and make it

easier for governments to

keep itinerant herders out

The Tuareg, the nomadic camel herders and traders of the Sahara who speak a dialect of the Berber language (Tamasheq), are also at risk of statelessness in West Africa. Demands for Tuareg self-determination date back to the 1950s, but no state was created for them when the colonial powers withdrew, and today they are spread among Algeria, Libya, Mali and Niger. Resentment at repression and marginalization of the desert regions were among the factors in the eruption of rebellions in Niger and Mali in the 1960s and again the 1990s, and in Mali in 2011. Lack of access to documents confirming their nationality remains a critical problem for many Tuareg. Other groups with a traditionally nomadic lifestyle face similar problems, such as the Mahamid Arabs settled in Niger, who are believed to originate from neighbouring Chad.

Historically, West African nomads have been able to survive or even thrive without identity documents confirming a nationality. State institutions may barely exist in remote rural or desert regions, meaning that they have little incentive or opportunity to register births and obtain identity documents in order to access public services. However, both security concerns and the desire to strengthen services have made identity documents more essential, even for those who do not wish to leave their own communities. If parents do not have documents, it is harder to register the births of children. The risk of statelessness increases with each undocumented generation.

This contribution is licensed under the following copyright licence: CC-BY 4.0

The article was published in the Atlas of the Stateless in English, French, and German.