Share Twitter Facebook Email Copy URL

This article is part of our series dedicated to the 75th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Why it matters for international actors

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) stresses that all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights (art. 1) and therefore entitled to the rights and freedoms subsequently outlined in the declaration, without “distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status”(art. 2). Sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, and sex characteristics (SOGIESC)[1] were not included as specific markers of potential discrimination in Article 2 or elsewhere in the UDHR, nor are they specifically mentioned in other international human rights frameworks.

Today, the majority of UN members states—129—no longer outlaw homosexuality, while 62 member states, predominantly African states and members of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), continue to criminalize consensual same-sex sexual acts. Discrimination on the grounds of SOGIESC has been discussed at the UN level since the 1994 Toonen v. Australia case and was included into several resolutions at the UN General Assembly and the Human Rights Council (HRC) over the course of the past 20 years.[2] These resolutions have been sponsored by 96 member states – a substantial majority – but were also met with strong opposition from over 50 member states, while over 40 member states abstained. To date, the UDHR and other human rights documents have not been amended to include SOGIESC as specific grounds of discrimination.

At the national level, constitutional protection against discrimination based on sexual orientation is only included in a dozen member states, and on gender identity only in a handful of member states. Instead, several states include protection clauses against discrimination on the grounds of SOGIESC linked to different social and economic rights in their national legal frameworks.[3] Additionally, 33 member states have included full marriage equality into their legal frameworks, which is only a quarter of the states that do not criminalize homosexuality.

While the majority of member states have decriminalized homosexuality and vocally support non-discrimination on the grounds of SOGIESC in international human rights fora, LGBTIQ+ people are still waiting for the explicit inclusion of non-discrimination based on SOGIESC into national, regional, and international legal frameworks. What does that mean for the full realization of the protection of the human rights of people with diverse SOGIESC globally? What roles should international actors play in supporting people with diverse SOGIESC – and which of these roles are realizable in adverse contexts? In light of the potential mismatch between expectations and reality, how can humanitarian and development actors, deployed to protect the human rights of all, best include LGBTIQ+ people?

Since the shift from needs-based to rights-based and localization-oriented programming in the 1990s, civil society organizations (CSOs) have become indispensable partners for international humanitarian and development actors. Often, local human rights CSOs represent first points of contact when accessing marginalized groups; however, their benefits as long-term partners for international actors are often overlooked. International interventions inclusive of SOGIESC rights might use LGBTIQ+ CSOs as entry points while failing to recognise the expertise and understanding of the local context that they can offer as partners. The success of inclusive humanitarian and development programming is reliant on meaningful partnerships between international actors and local CSOs that go beyond colonial power structures and hierarchies. Therefore, the realization of Article 20 of the UDHR – the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association – is essential for the protection and fulfillment of the human rights of people with diverse SOGIESC, along with other marginalized groups. Its realization allows LGBTIQ+ people to organize and voice political demands, but also to create communities and establish chosen families that help to reduce risks and increase individuals capacities and resilience in times of crisis and instability.[4] Through the right to freedom of association, people with diverse SOGIESC are able to gather in safe spaces such as LGBTIQ+ community centers, cafés, and bars without fear of discrimination, harassment, or other forms of violence. Inclusive humanitarian and development programming hugely benefits from access to CSO networks with which they can partner.

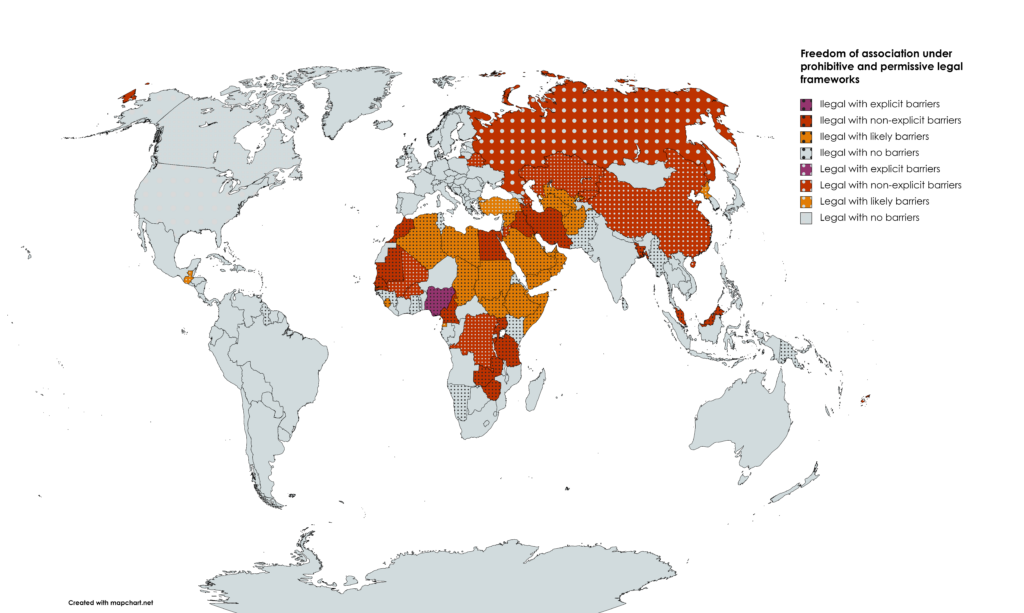

Unfortunately, freedom of peaceful assembly and association is not guaranteed for people with diverse SOGIESC in 57 UN member states. Among those, 31 countries exhibit confirmed legal barriers, and 26 others likely barriers for LGBTIQ+ CSOs. Multiple reasons for this exist: A number of these countries are authoritarian states that restrict or outright prohibit most political and human rights CSOs, for instance the Gulf states, China, and Russia. Additionally, in some of these 57 member states, same-sex relations are criminalized – and some of these, the related legal frameworks also prohibit LGBTIQ+ CSOs.

While overall restrictions on CSOs and the criminalization of same-sex relations overlap in some cases (notably, when it comes to the Gulf states and some other members of the OIC), the same is not the case for all states with legal barriers for LGBTIQ+ CSOs. For instance, in Burkina Faso, China, the DRC, Guatemala, Mali, Russia, and Turkey, such legal barriers exist, but same-sex relations are not explicitly outlawed. Restrictions to the freedom of assembly and association might be used to curtail the human rights of people with diverse SOGIESC instead of directly outlawing same-sex relations as the following four examples extracted from the ILGA World Database (2023) highlight: In the DRC, where same-sex relations have never been criminalized, CSOs need to first be approved by the respective ministry linked to the sector of their engagement and then by the Minister of Justice. According to a joint submission by 6 NGOs to the 2017 Universal Periodic Review (UPR), most organizations referencing LGBT people in their constitutions have been denied registration. Similarly, in Guatemala, same-sex relations have never been criminalized since independence in 1834, but Article 15 of the Law on Non-Governmental Organizations (2020) “allows the Government to close NGOs and pursue criminal charges against their directors for using external donations or funding for the purpose of altering the public order”. This is applied to SOGIESC CSOs. In China and Russia, where same-sex relations have officially been decriminalized in the 1990s, similar non-explicit legal barriers exist to the creation and maintenance of LGBTIQ+ CSOs. In Russia, LGBTIQ+ activists and CSOs are generally labeled and prosecuted as foreign agents which can even lead to them being charged as terrorists. In China, CSOs “shall not endanger the social interest … and not breech social ethics and morality”. As a result, the registration of CSOs referring to sexual diversity has been rejected, thereby preventing access to public funds.

Even when governments do not explicitly prohibit same-sex relations, humanitarian and development actors leading LGBTIQ+ inclusive programming face difficulties to reach target communities. In order words, legislation preventing the registration of LGBTIQ+ CSOs harms the implantability of rights-based humanitarian and development interventions focused on empowering marginalized people with diverse SOGIESC. Instead, although limited, reaching parts of this population is sometimes possible through needs-based rather than rights-based programming. Programming on the prevention of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) has been used to contact men who have sex with men as well as trans women but does not reach lesbian or bisexual women and gender-diverse people assigned female at birth. As previous research showed for the case of China, CSOs registered with the purpose of HIV/AIDS prevention became spaces for GBQ men that were supported by international public health organizations; however, LBQ women remained marginalized, invisible, and underfunded, because similar avenues to registering CSOs were not available to them. Additionally, existing programming around sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), including prevention and the protection of survivors, is often targeting women and people assigned female at birth. To date, SOGIESC issues are not often taken into consideration in these spaces, nor are humanitarian and development staff necessarily trained on the needs of people with diverse SOGIESC. However, SGBV programming could potentially be used as an entry strategy into marginalized communities, including LBQ women.

In contexts where same-sex relations and the expression of diverse genders are prohibited, but the registration and activities of SOGIESC CSOs are not, related advocacy is possible. Through targeted efforts, these CSOs have been successful at slowly shifting social norms towards greater acceptance of people with diverse SOGIESC which, in turn, might lead to legal changes, as the case of Guyana shows. However, as outlined within the Humanitarian Principles, neutrality is central to the successful work of humanitarian organizations which prevents them from openly supporting LGBTIQ+ CSOs at the national or regional level when SOGIESC rights are not legally guaranteed. The need to maintain access and ensure the safety of both staff and local communities is prioritized here over participating in local advocacy movements.

When legal frameworks punish same-sex relations while also preventing the creation of LGBTIQ+ CSOs, humanitarian and development organizations must be particularly mindful of considering the do no harm principle. It obliges their workers “to prevent and mitigate any negative impact of their actions on affected populations”. When applying this to inclusive humanitarian and development programming, considering the local political, legal, and socio-cultural contexts is crucial for preventing harmful consequences. Reaching local LGBTIQ+ people might seem essential for the implementation of rights-based approaches aimed at their empowerment, but this can be dangerous people with diverse SOGIESC are criminalized, and “perpetrators” given prison sentences or even subjected to the death penalty. Unfortunately, as highlighted in a report by International Alert, people with diverse SOGIESC in situations of conflict and displacement face even greater vulnerability, precarity, and risks of violence than in peace times, as they find themselves in unknown circumstances surrounded by potentially hostile strangers. The authors stress: “Forcibly or accidentally outing people whose social or physical survival may depend on a degree of invisibility in terms of their SOGI can have grave consequences” (p. 32). Additionally, organizations openly working on SOGIESC issues might also experience backlash and put their staff at risk when operating in adverse contexts. Therefore, alternative entry routes and programming can be essential to reach people with diverse SOGIESC in countries with prohibitionist legal frameworks.

While LGBTIQ+ rights are increasingly perceived as human rights on a global level, most international human rights documents, including the UDHR, do not specifically mention sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, or sex characteristics as specific grounds of discrimination. This is particularly important when considering the protection of people with diverse SOGIESC during humanitarian and development programming. Inclusive programming is highly dependent on the presence of local LGBTIQ+ CSOs. These represent entry points for humanitarian and development actors attempting to identify community needs, but can also act as long-term partners to ensure localized, rights-based programming. Unfortunately, some 57 states restrict the freedom of peaceful assembly and association of LGBTIQ+ people, thereby preventing the registration and maintenance of SOGIESC CSOs. This violation of Article 20 of the UDHR effectively harms the creation of a vibrant LGBTIQ+ community gathering in safe spaces and thereby makes the organization of political demands difficult, even when homosexuality is not prohibited. The protection of SOGIESC rights as human rights through inclusive humanitarian and development programming relies on the full realization of the right to freedom to peaceful assembly and association.

Dr Mira Fey is a researcher and educator working on gender and sexuality with a focus on rights protection and violence prevention. In collaboration with Rosalux Geneva, she has previously conducted a study on the employment situation of gender-diverse workers in International Geneva and is currently looking at SOGIESC inclusion within international trade union federations. Lizzie Wright specialises in diverse SOGEISC inclusion in humanitarian response and currently works for an INGO. She is passionate about bringing intersectional and decolonial perspectives into humanitarian programming. Cover picture by Bettina Jacot-Descombes / Geneva Pride 2023

[1] People with diverse SOGIESC is used here as a complement to LGBTIQ+ people (Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, intersex, queer, and other people with diverse SOGIESC). We consider people with diverse SOGIESC to be more inclusive and less centered around identity.

[2] The UN General Assembly explicitly included sexual orientation as a ground for discrimination in 2003 in a resolution on Extrajudicial, summary, or arbitrary executions, with a reference to the UDHR and the right to life, liberty and security of all (art. 3). Subsequent iterations of this resolution have also included gender identity (since 2012). The first Human Rights Council (HRC) resolution focusing on the discrimination of, and violence committed against people based on their sexual orientation and gender identity was adopted in 2011 – 63 years after the creation of the UDHR. Some European human rights treaties now include specific mentions to sexual orientation, but not gender identity and expression or sex characteristics.

[3] These rights are outlined articles 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, and 26 of the UDHR. Data on legal provisions against discrimination based on SOGIESC are available for education, employment, health, housing, and the provision of goods and services.

[4] To move away from framing marginalized groups as victims only, including capacities in needs assessment frameworks is essential.

This article is part of our series dedicated to the 75th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.