Share Twitter Facebook Email Copy URL

The rise of nationalism and xenophobia in some countries is leading governments to consider changes to the rules governing citizenship there. That causes problems for migrants and their descendants. A constitutional change in the Dominican Republic revoked the citizenship of hundreds of thousands people of Haitian origin. Local and international pressure has restored those rights for only half of them.

An amendment to the constitution that came into force in 2010 deprived around 250,000 people in the Dominican Republic of their citizenship. This decision, signed by 209 of the 215 senators and deputies in the legislature, made a quarter of a million people stateless in one fell swoop. The people affected were children born in the Dominican Republic whose parents had immigrated from neighbouring Haiti.

The amendment changed the territorial principle – the rule that had held since the country’s founding in 1844 constitutionally entitling anyone born within its borders to Dominican citizenship. In constitutional law, this principle is called jus soli, Latin for “right of the land”. But in 2010, Article 18 of the constitution switched that to jus sanguinis, or the “right of blood”. According to this principle, a Dominican is the daughter or son of a Dominican mother or father. This new rule also applied to persons who held Dominican citizenship when the constitutional change came into force. A new paragraph excluded those who were in the country illegally before the deadline, in particular the “Haitianos” from next door.

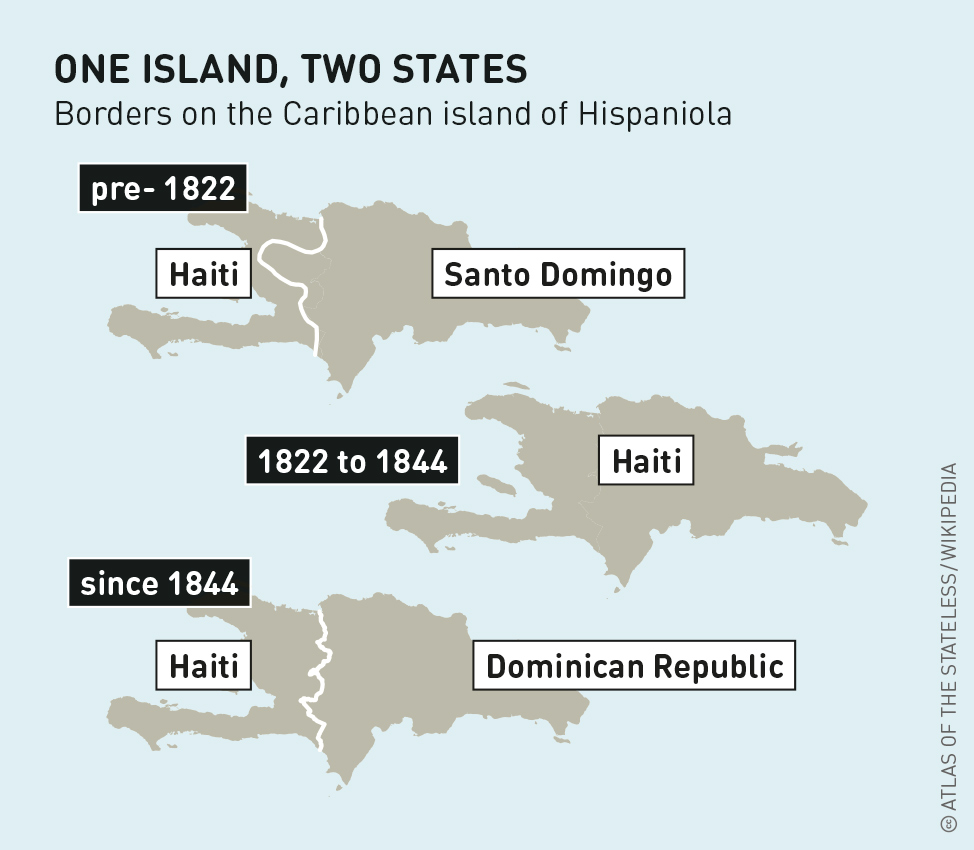

Hispaniola has been centrally governed and split

up several times. The Tensions still remain

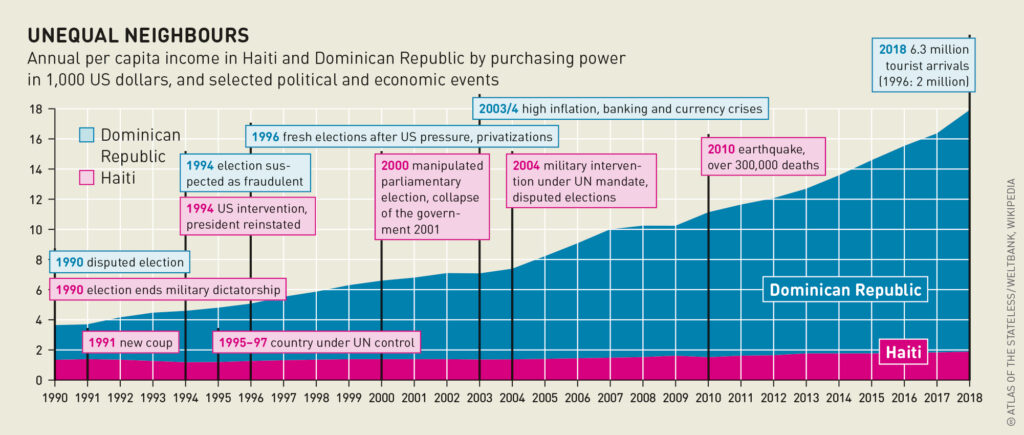

The Dominican Republic and Haiti share the second-largest island in the Caribbean. The western part of the island, Haiti, is linguistically and culturally francophone and is dominated by people of African descent. The east, the Dominican Republic, is Hispanic. The relationship between the two states has been tense since the Dominicans fought for independence from Haiti in 1844. At the same time, Haiti is one of the poorest countries in the Western Hemisphere. Its per-capita income is one-tenth of that in the Dominican Republic. Around one-fifth of its population live below the poverty line.

Such differences have led, and still lead, to people migrating from Haiti into the neighbouring Dominican Republic in search of work, especially in construction and farming. According to the Dominican office of statistics, 87 percent of the 571,000 foreigners living in the country come from Haiti, along with an unrecorded number of illegal and temporary migrant labourers. The majority of migrants from Haiti who are affected by the new rules arrived after the 1930s on the basis of bilateral agreements. They were employed as braceros, or day-labourers, to harvest sugarcane. They were originally permitted to stay for the duration of the harvest season, but the rules were relaxed by the Dominican authorities because of the year-round demand for labour in the sugarcane industry. The workers’ families settled near the cane fields and processing mills in separate bateys, or simple settlements. Despite a certain amount of discrimination as a result of their darker skin or French-sounding names, their descendants were not only tolerated but were registered as Dominican citizens. Under the old constitution, they received the birth certificates and identity documents they needed to enroll in schools, visit hospitals, open bank accounts and conduct financial transactions.

agricultural export powerhouse. Now it is

the tourist industry that needs workers

The residency and citizenship of the Haitanos were repeatedly questioned by Dominican nationalists, but their legal status remained untouched. This changed with the arrival of nationalist parties in the government at the start of the 2000s. Local offices of the central election authority began to question the validity of identity documents and started labelling them as “unjustified”. Identity documents known as cedulas were confiscated or not renewed, and birth certificates were not issued.

Those affected organized themselves and lodged complaints about the denial of Dominican citizenship in the national courts and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. In 2013, the Supreme Constitutional Court in Santo Domingo tightened the rules again. The Court ruled that the new provisions on citizenship be applied retroactively to 1929 – a clear violation of the globally recognized prohibition against retroactive effects. In response to international protests, the Dominican government and both chambers of parliament passed a modified naturalization law. People whom the new law regarded as “illegal persons” but were registered with the civil registry office could be recognized as Dominican citizens. In addition, Haitanos whose birth was not registered in Haiti and who lacked a connection to the land of their ancestry could be naturalized within two years.

Nevertheless, civil society organizations point out that five years on, around 50 percent of the 245,000 or so people affected still lack birth certificates and identity documents because no final decisions could be made on their cases under the current regulations. These people are still subject to official arbitrariness and bureaucratic trickery – such as the rejection of original documents as forgeries or the refusal to issue residency permits to prevent them from being recognized as Dominican citizens.

Here, 20 percent of the population

is very poor; in Haiti the figure is 60 percent

This contribution is licensed under the following copyright licence: CC-BY 4.0

The article was published in the Atlas of the Stateless in English, French, and German.