Share Twitter Facebook Email Copy URL

A balance sheet one year into the COVID-19 crisis

The COVID-19 crisis has highlighted how governments’ approaches to workers’ health and safety have fallen short in preventing the spread of the virus and protecting its citizens in the world of work. Instead of protecting so-called ‘essential’ workers, governments and businesses left low-paid workers such as care workers, supermarket staff, warehouse, agricultural workers, and cleaners defenceless in the face of the rapidly spreading virus.

According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO) and World Health Organisation (WHO), up to 20-30 per cent of COVID-19 cases may be attributed to exposure at work[1]. Business opposition to mandatory testing, inadequate remote working policies and above all the lack of provision of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) have only exacerbated the public health crisis.

Thus, the on-going COVID-19 pandemic has created new challenges as well as opportunities for trade unions, social movements and progressive forces who want to put public health above private profits.

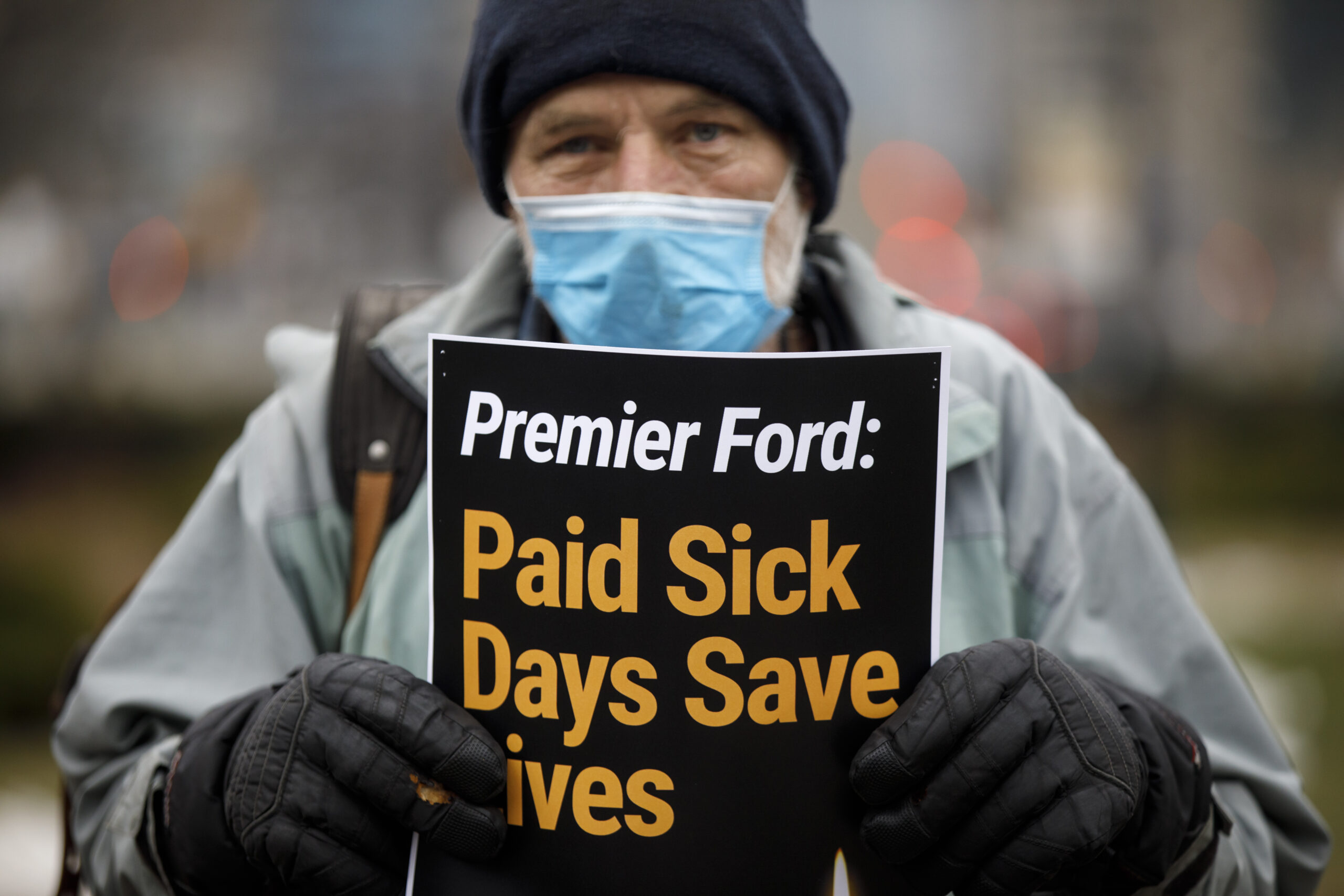

The struggle over sick pay

For decades employers have preached ‘presenteeism’ to its workforce. Unsurprisingly, workers continued to turn up to work despite having COVID-19 symptoms during the first wave in 2020. The lack of statutory sick pay from day one as well as the fear of being reprimanded for being sick led to a high percentage of COVID-19 cases among low-wage workers. Only a minority of businesses introduced new sick leave policies so that employees could call in sick even at the slightest sign of a cold and are reimbursed for the time off.[2] In many cases, these policies did not apply to part-time workers and newer employees who are dependent upon working more hours to make a living wage.

Countries’ adoption of COVID-19 as an ‘occupational disease’ or ‘accident at work’ has been a lifeline for these precarious workers. It has allowed them to access compensation for loss of income and obtain sick pay. However, this was not the case from the outset. Workers and unions have had to fight hard for this. The British union GMB, for example, had to first win full sick pay for subcontracted hospital workers such as cleaners, porters, caterers and security guards working for Sodexo and ISS[3]. Across the Atlantic, New York City public school teachers had to threaten with a ‘mass sick-out’ to force Mayor Bill de Blasio to close the schools[4].

Even for those workers entitled to sick pay, the burden of proof lies with them. This allows employers to abdicate responsibility and externalise costs. As it remains too early to tell whether those suffering with long-term side-effects – also known as ‘long COVID-19’ – will be able to access compensation, political and legal battles over the burden of proof are likely to ensue.

Persistent Inequalities

Italy’s agricultural sector employs approximately 120,000 migrant workers. While Eastern European workers were quick to return home at the outbreak of the pandemic, African migrant workers remained stuck in camps without access to clean water or electricity. Instead of providing PPE and sanitary measures, employers and government ‘outsourced’ the provision of PPE to aid and church groups[5]. In Germany, ten thousand of Bulgarian and Romanian seasonal workers were flown in to pick asparagus. In both countries, the sanitary situation in the barracks was so abysmal that migrant workers were forced to take strike action over pay and their living conditions. Both cases underline how governments’ systematic under-financing of labour inspectorates and ‘outsourcing’ of welfare provision and ‘test and trace’-systems only complicated the containment of the COVID-19 crisis.

The failure to contain the virus has become most pronounced in the social care and healthcare sectors. Amnesty International, UNI Global Union and Public Services International have estimated that a total of 7000 healthcare workers have so far died of COVID-19 across the globe[6]. According to the ILO, more than 136 million workers in health, care, and social work are at serious risk of catching COVID-19 in the workplace[7]. In many countries, priority lists for PPE equipped medical doctors and nurses with PPE but let down care workers in nursing homes or homecare workers. Amongst other reasons, this turned nursing homes into deaths traps for care-users. Despite the general public’s support for these workers, the divide between medical professions and those deemed ‘care work’ has deepened during the pandemic.

Concurrently, the COVID-19 crisis re-entrenched existing gendered divisions of labour. A disproportionate burden has been placed on women who have had to work in so-called essential services, been the ones who have had to deal with children being at home due to school closures and have had to face the stress of having an older relative in a care home. Moreover, it has been reported that the number of domestic violence cases have risen sharply, underlining the need for the ILO’s Convention 190 on violence and harassment in the world of work.

It is not only the gendered division of labour that has manifested itself in novel ways but also the racialized division of labour. In the UK, Black and Asian (BAME) healthcare staff have been more likely to catch the virus and to die from it across all professional groups within the NHS[8]. On the one hand, this is because of the racialized division of labour within healthcare, where many frontline staff are People of Colour – both migrant and native-born. The high infection rate and the severity of the disease can also be traced back to BAME healthcare staff being more likely to suffer from hypertension[9], diabetes[10] and coronary heart disease, all of which are associated with racialisation and experiences of racism. These experiences of racism do not only worsen physical health outcomes but also people’s mental health, which will be addressed further below.

The crisis of remote work

During the pandemic, office workers and white-collar employees were sent home to limit the spread of the virus. Remote working became the norm for those who were not working on the frontlines or deemed ‘essential’. This has deepened existing the divisions of labour between ‘white collar’ workers and so-called ‘blue’ and ‘pink collar’ workers.

Nevertheless, even among remote workers considerable differences can be observed. While some workers have been able to transform their spare room into an office space, others are hunched in front of their laptops working in their kitchen with books stacked under their computer screens. Furthermore, organisational support for these remote workers takes a variety of forms but by no means amounts to the kind of social networks and cooperation that a work environment engenders. While office spaces are far from perfect, remote working isolates people even further from their colleagues and above all undermines the cooperative and collective aspect of work. The usual chat in between work meetings and the exchange with colleagues has given way to an endless stream of Zoom meetings and E-Mail exchanges.

Thus, it would be reductionist to label remote workers the winners of this crisis. Employers’ re-organisation of office has instead accelerated the on-going mental health crisis, which is costing our economies dearly. Back in the fiscal year of 2018-2019, Britain’s Health & Safety Executive reported that 12.8 million workdays had been lost due stress, anxiety, or depression[11] while only 273,000 working days were lost due to labour disputes, the sixth-lowest annual total since records began in 1891[12]. In Japan, employees’ insomnia and sleeplessness costs the economy $138bn a year[13].

Zoomed Out

Yet once again, legislation and regulation have to catch-up to the new reality of what cyber-psychologist Dr Linda Kaye has labelled ‘Zoom fatigue’. Such ‘technostress’ has grown largely due to the lack of downtime between different work tasks as well as over-scheduling. Moreover, several studies have confirmed that remote workers end up working longer hours in spite of this neither improving our productivity nor employee well-being[14].

‘Zoom fatigue’ or ‘technostress’ are also a by-product of workers’ cameras always being on. This creates a heightened sense of self-awareness[15] as persons can no longer rely on social cues and non-verbal communication central to in-person communication. In this context, it is unsurprising that 65 per cent of enterprises have argued that it has become difficult to sustain morale[16].

Capital’s answer to the mental health crisis has been to offer yoga, wellness, and resilience trainings for employees. Among the latest trends are gong baths[17] and holding a sixty-second-long mindfulness session before the next meeting. During the Brexit negotiations, British civil servants dealing with a no-deal Brexit scenario were being provided with mental health, stress support, and onsite wellbeing exercises[18]. Meanwhile in Japan, companies are giving their employees time to nap during the day and ‘sleep while present’ (inemuri), further blurring the lines between work and rest time. Such approaches are also finding their way into sectors such as the US restaurant industry where the majority of staff does not even earn the statutory minimum wage[19].

Parameters of a Progressive Health & Safety Agenda

Faced with such challenges, how can trade unions, social movements, and the left develop a progressive agenda on workers’ health and safety?

Trade unions need to throw their weight behind workers who raise health and safety concerns within the workplace. Workers heightened awareness around health and safety issues can contribute to rebuilding the labour movement and stop the decline in trade union membership. Supporting and organising workers over health and safety issues can also rebuild much-needed workplace union structures, which have been eroding since at least the early 1980s.

Trade unions could also start framing their health and safety proposals for ‘essential’ workers as central to promoting public health. Meanwhile, the left can play a role in bringing workers’ health and safety issues into the growing movements for public health. In doing so, it could give rise to new alliances for public health that bring together workers, consumer groups and social movements. Such alliances are needed so that governments and employers take the necessary preventive measures so that the mistakes of the COVID-19 crisis are never repeated.

As this article has shown progressive health and safety policies, protocols and measures also need to account for gendered and racialized divisions of labour in the workplace and across our economies. As the European Union’s approach to health and safety enshrined in the 1989 OSH directive (89/391/ECC) does not include the ‘self-employed’, the current legal framework continues to create an insider-outsider divide which has plagued industrial relations for far too long. Going forward, progressive trade unions, social movements, and the left need to advocate for health and safety policies that do not deepen existing divisions of labour and are simultaneously extended to all groups of workers, including informal workers, part-time workers and to those workers who have been mis-categorised as ‘self-employed’.

The growth of such informal, atypical employment relations has resulted in an increasing number of workers being excluded from the remit of health and safety regulation. Progressive health and safety frameworks need to go hand in hand with other labour market policies, which aim to close the legal loopholes that enable companies to minimise their overhead costs by categorising workers who are central to their business model as ‘self-employed’.

In the past, the above-mentioned psychosocial risks were indirectly addressed through regulating working hours and rest periods. Today, companies have convinced the general public that mental health issues are an individual’s responsibility that can be addressed by a combination of wellness, mindfulness and therapy. This mirrors the present power imbalance between capital and labour.

Progressive social movements and the left have already joined forced to de-stigmatise mental health issues. Through worker organising and collective agreements, trade unions can ensure that companies and employers address both individuals’ mental health needs and at the same time offer a collective response to alleviate stress, over-scheduling, and long work hours.

Despite all the persistent challenges, the COVID-19 crisis has brought the fight for public health and workers’ health and safety closer together, but it will require organisation, strong collective agreements and a holistic perspective to win for workers.

[1] Anticipate, prepare and respond to crises: Invest now in resilient OSH systems International Labour Office – Geneva: ILO, 2021 https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_dialogue/—lab_admin/documents/publication/wcms_780478.pdf

[2] Kate Taylor and Hayley Peterson (2020) Trader Joe’s is giving employees additional paid sick time to ensure they stay home when ill during coronavirus outbreak, and it’s a brilliant business strategy, Business Insider 5 March 2020, source: https://www.businessinsider.com/trader-joes-employees-additional-paid-sick-time-coronavirus-2020-3?utmSource=twitter&utmContent=referral&utmTerm=topbar&referrer=twitter&r=US&IR=T

[3] GMB win as Sodexo pledge full pay for all health workers from day one, GMB London 4 March 2020, source: https://www.gmblondon.org.uk/news/gmb-win-as-sodexo-pledge-full-pay-for-all-health-workers-from-day-one.html

[4] Susan Edelmann (2020) NYC teachers planning ‘mass sickout’ over de Blasio’s refusal to close schools, New York Post 14 March 2020, source: https://nypost.com/2020/03/14/nyc-teachers-planning-mass-sickout-over-de-blasios-refusal-to-close-schools

[5] Elisa Oddone (2020) Coronavirus fears for Italy’s exploited African fruit pickers, Al-Jazeera English 19 March 2020, source: https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2020/3/19/coronavirus-fears-for-italys-exploited-african-fruit-pickers

[6] COVID-19: Health worker death toll rises to at least 17000 as organizations call for rapid vaccine rollout, Amnesty International 5 March 2021, source: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/03/covid19-health-worker-death-toll-rises-to-at-least-17000-as-organizations-call-for-rapid-vaccine-rollout/

[7] Anticipate, prepare and respond to crises: Invest now in resilient OSH systems International Labour Office – Geneva: ILO, 2021 https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_dialogue/—lab_admin/documents/publication/wcms_780478.pdf

[8] Tim Cook, Emira Kursumovic, Simon Lennane (2020) Exclusive: deaths of NHS staff from covid-19 analysed, 22 April 2020 HSJ, source: https://www.hsj.co.uk/exclusive-deaths-of-nhs-staff-from-Covid-19-analysed/7027471.article

[9] Elizabeth Brondolo, Erica E. Love, Melissa Pencille, Antoinette Schoenthaler, Gbenga Ogedegbe, Racism and Hypertension: A Review of the Empirical Evidence and Implications for Clinical Practice, American Journal of Hypertension, Volume 24, Issue 5, May 2011, Pages 518–529, https://doi.org/10.1038/ajh.2011.9

[10] Andrew John Karter, Race and Ethnicity, Vital constructs for diabetes research, Diabetes Care 2003 Jul; 26(7): 2189-2193, https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.26.7.2189

[11] Health and safety at work Summary statistics for Great Britain 2019, source https://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/overall/hssh1819.pdf

[12]Office of National Statistics (ONS), Labour disputes in the UK: 2018 Analysis of UK labour disputes in 2018, including working days lost, stoppages and workers involved, source, https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/workplacedisputesandworkingconditions/articles/labourdisputes/2018

[13] RAND Europe: Why Sleep Matters: Quantifying the Economic Costs of Insufficient Sleep, source: https://www.rand.org/randeurope/research/projects/the-value-of-the-sleep-economy.html

[14] Peter Fleming (2018) Do you work more than 39 hours a week? Your job could be killing you, The Guardian 15 Jan 2018, source: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2018/jan/15/is-28-hours-ideal-working-week-for-healthy-life

[15] Linda Kaye (2020) The psychology behind ‘Zoom fatigue’ explained, source: https://www.edgehill.ac.uk/news/2020/04/the-psychology-behind-zoom-fatigue-explained/?cn-reloaded=1#gref

[16] Anticipate, prepare and respond to crises: Invest now in resilient OSH systems International Labour Office – Geneva: ILO, 2021 https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_dialogue/—lab_admin/documents/publication/wcms_780478.pdf

[17] Bruce Daisley (2019) Why stressed workers need four-day weeks – not wellness trends, The Guardian 28 Aug 2019, source: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/shortcuts/2019/aug/28/gong-baths-work-stress-pressure-four-day-week-working-hours-wellness

[18] Mattha Busby (2019) Civil servants handling no-deal plans offered mental health support, The Guardian 4 April 2019 https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/apr/04/civil-servants-no-deal-brexit-mental-health-support-defra?CMP=share_btn_tw

[19] Kim Severson (2020) The Hard-Knocks Restaurant World Discovers Wellness, NY Times 3 March 2020, source: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/02/dining/health-and-wellness-restaurants.html

Mark Bergfeld is the Director of Property Services & UNICARE (private care and social insurance sector) at UNI Global Union - Europa.