Share Twitter Facebook Email Copy URL

The drawing of boundaries early in the last century left bitter legacies. Thousands of people who were born in Kuwait and have lived there all their lives cannot claim Kuwaiti nationality. They are deprived of basic rights – to vote, enroll in a public school, or travel. And they are fated to pass on their statelessness to their children and children’s children.

When the 2011 Arab Spring shook up capital cities in North Africa and the Middle East, people also took to the streets in Kuwait. In February 2011, about 1,000 people gathered to demand more rights. But unlike Cairo or Tunis it was not about the disposal of a ruler the people did not want, it was about becoming a citizen of the country. The government sent security forces to confront protestors who were not considered citizens of Kuwait. Several protesters were jailed; dozens were injured.

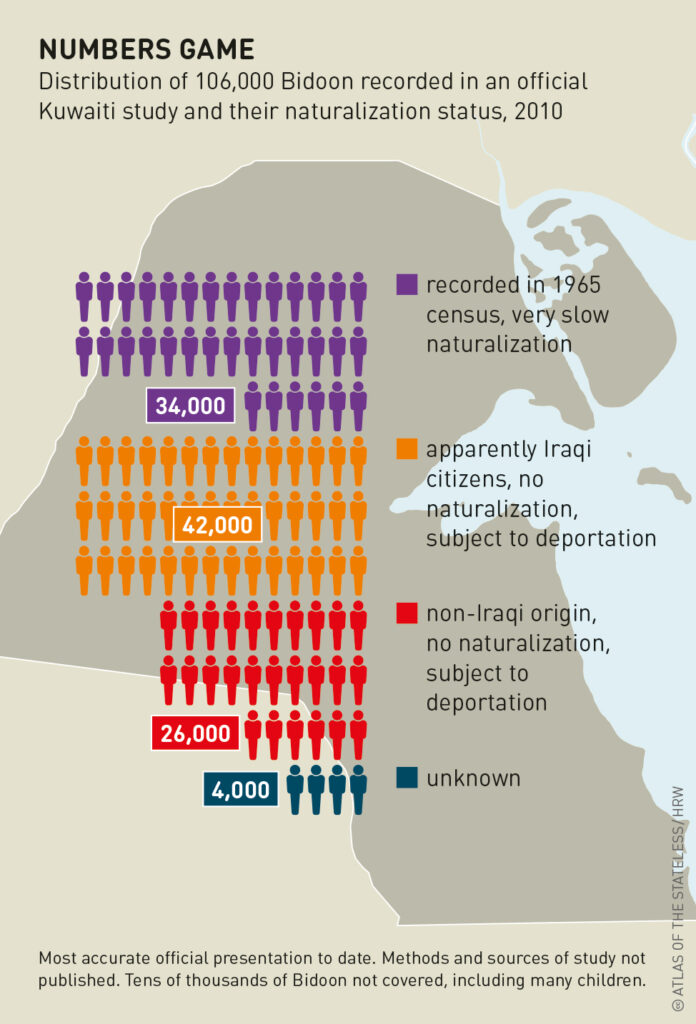

The protesters were Bidoon, a group of people who have for nearly 60 years suffered from a particular form of statelessness. There are no official figures, but an estimated 100,000 to 200,000 Bidoon are believed to live in the Gulf region. According to the Kuwaiti government, the Bidoon are not really Kuwaiti, but foreigners who entered the country without authorization. The ancestors of the Bidoon were nomadic Bedouins who did not register with the Citizenship Committees when Kuwait became independent in 1961. The reasons for this were manifold – illiteracy, homelessness, poverty or lack of access to authorities – and the fact that the borders of the new Gulf sheikdoms were hardly secured or even marked at that time. Apart from Kuwait, the Bidoon also live in the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain.

The consequences of exclusion by Kuwaiti authorities are serious. The Bidoon have no civil rights, are not allowed to vote, and are excluded from most social benefits. According to the Lebanon-based Gulf Centre for Human Rights, the situation is particularly discriminatory for Bidoon children and women. Amnesty International says that despite a legislative reform in 2015, the Bidoon continue to face “severe restrictions on their ability to access documentation, employment, healthcare, education and state support enjoyed by Kuwaiti citizens”. In February 2019, the Kuwaiti Minister of Education rejected a parliamentary proposal to enrol the children of Bidoon in public schools. Registration was permitted only for those Bidoon children whose mothers were Kuwaiti citizens, or children and grandchildren of Bidoon who were classified as “martyrs” after the 1990 Iraqi invasion. Bidoon women and women married to Bidoon men are subject to sexual harassment at the hands of the authorities. Women harassed when applying for documents were unaware of any avenues to complain, according to a British Home Office report in 2016.

the numbers of stateless Bidoon because they

are considered tolerated illegal residents

In a 2017 report, the Swedish Immigration Service described the system of registration in Kuwait as complicated. Instead of a passport, the Bidoon receive a “review” or a “security card”. This is necessary to apply for a birth certificate, withdraw money from a bank, drive a car or consult a doctor. Bidoon whom the authorities believe to have a different nationality, such as Iraqi, Iranian, Saudi or Syrian, are issued with a card with a blue stripe, valid for six months and extendible for another six. During this time, the person’s nationality is examined and may be determined. Certain advantages are envisaged for holders of such cards, such as the possibility of a five-year residence permit. Bidoon are also be subject to travel restrictions: they must apply for an “Article 17 Passport”, issued on a case-by-case basis allowing them to travel; Kuwait reserves the right to refuse their re-entry.

an opaque manner, leaving

the people affected in the dark

The manner in which the Kuwaiti authorities determine that a Bidoon may have a different citizenship is questionable. According to a December 2018 report by Al Jazeera, a Bidoon named Ahmed applied for a “security” card. When he received the card, he found that it stated that his father was an Iraqi citizen – even though he had documents showing he was Kuwaiti. The authorities refused to clarify the matter, despite Ahmed’s repeated requests.

The Emir of Kuwait, Sheikh Jaber al-Ahmad al-Sabah, issued a decree in 1999 that makes the naturalization of 2,000 Bidoon per year possible. However, research by the portal Inside Arabia shows that only three percent of the Bidoon in Kuwait had received citizenship by 2019. “By continuing to deny the Bidoon citizenship, the authorities are denying these long-term residents a range of basic rights, which in effect exclude them from being part and parcel of and contributing to a vibrant Kuwaiti society,” says Amnesty International.

means that little is known

about the location of many Bidoon

When a bomb attack on a mosque was carried out in 2015, the judiciary indicted 29 people and stated that 13 “illegal residents” were also on trial. They were Bidoon. In summer 2019, 15 Bidoon were arrested during a demonstration held after the suicide of a 20-year-old Bidoon, Ayed Hamad Moudath. The state had refused to issue him with identity papers, whereupon he had lost his job.

This contribution is licensed under the following copyright licence: CC-BY 4.0

The article was published in the Atlas of the Stateless in English, French, and German.