Share Twitter Facebook Email Copy URL

Switzerland: The “Group for a Switzerland without an Army” is perhaps the most successful disarmament organization in Europe. The Swiss organization has been launching peace policy debates for the last 40 years.

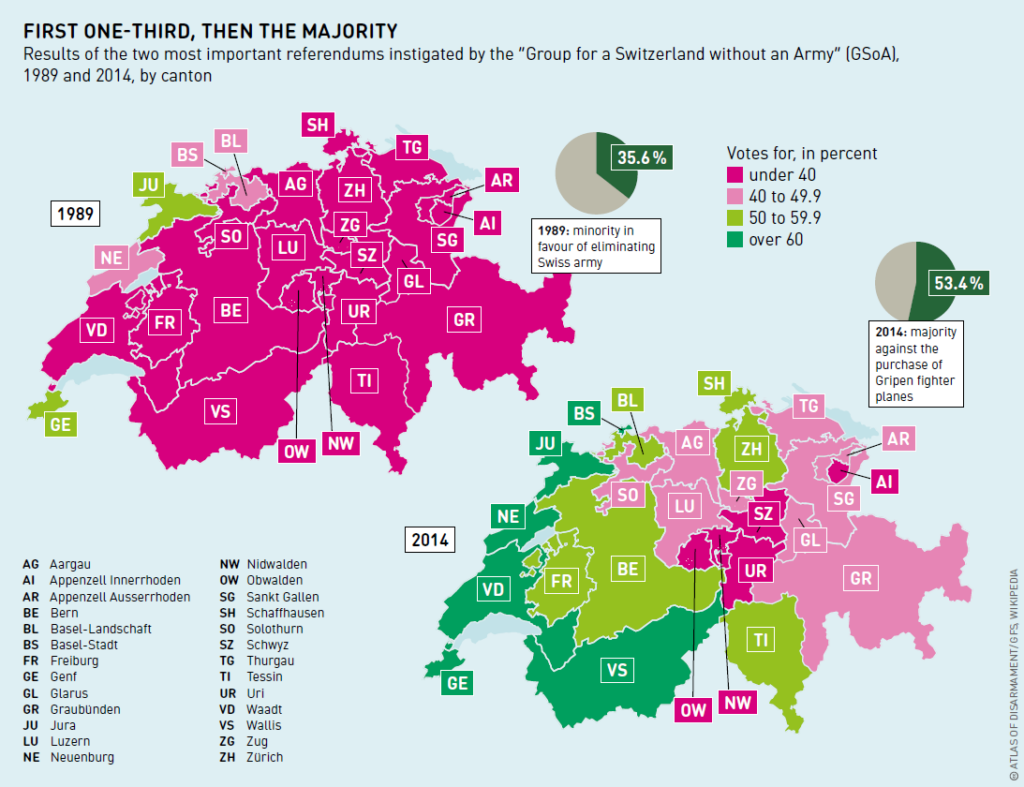

The debate ended with a clear defeat, on 26 November 1989, when 64.4 percent of Swiss voters said “no” to a popular initiative to abolish the country’s army. The revolution that the “Group for a Switzerland without an Army” (known by its German acronym GSoA) wanted to instigate was put on hold. But the vote still led to fundamental political and social changes in the role of the Swiss army.

First there was the fact that more than one-third of the voters, more than a million people, voted in favour of the GSoA initiative – a shock for the right-wing conservative power bloc. Before the vote, the Federal Council, the Swiss government, announced that Switzerland did not have an army: it was an army. The November 1989 vote, which followed an exceptionally emotional campaign, showed clearly that young people regarded the army not as a meaningful model but as a necessary evil.

Despite the defeat, the vote ushered in a whole series of reforms. In the following year, policymakers set peacebuilding as the army’s new task, increasingly putting domestic disaster assistance at the forefront. The number of military personnel fell sharply, from 780,000 in 1990, to 426,000 in 1995; today the figure is 150,000. Between 1968 and 1996, some 12,000 young men were jailed for refusing military service. This practice decreased noticeably after 1989; in 1996 young men were permitted to do community service instead of joining the army. In addition after 1989 a stint as an officer was no longer a prerequisite for a professional career.

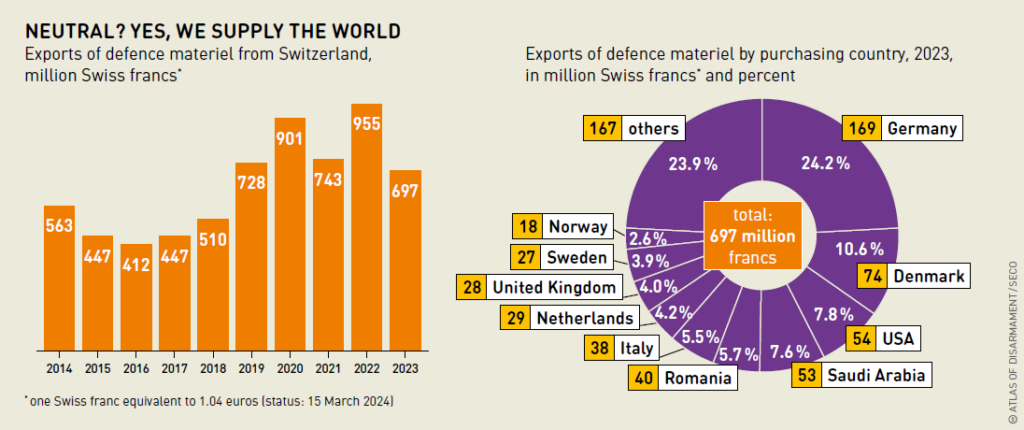

Around 85% go to NATO members

The abolition initiative of 1989 certainly left its mark on Switzerland. But the collapse of the Soviet Union had a much more dramatic influence on the country’s security policy and the makeup of its army. So too did the accompanying fundamental changes in the military and geopolitical situation in Europe.

The GSoA is organized on a grassroots democratic basis and is funded by donations. What distinguishes it is its stability. Its number of members has stayed steady at around 20,000 for years. In its over four decades of existence, it has brought seven popular initiatives (its own initiatives, which require collecting 100,000 citizens’ signatures), and two referenda (about laws, requiring 50,000 signatures) to the vote.

The GSoA makes strategic use of these two grassroots democracy mechanisms – a Swiss speciality. Gathering signatures and voting campaigns mobilize support and create media attention and political debates. The GSoA not only works towards its original goal, abolishing the army, but also tries to promote disarmament policies. Its aim is a stricter arms export control, or to stop them altogether. It wants to ban state-owned investors from investing in arms firms. In 1993, an initiative to stop the acquisition of 34 F/A-18 Hornet US fighter jets failed, but a referendum in 2014 against the purchase of 22 new Gripen fighters from Sweden was a sensational success. In 2023, a GSoA general assembly decided to launch an initiative to oblige Switzerland to sign the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

There has been a longstanding close cooperation on certain subjects between the GSoA and the two main political parties that are critical of the army, the Social Democrats and the Greens. It is not uncommon for politicians to start their careers with a spell of working with the GSoA. The two best-known examples of this are Jo Lang (Greens) and Andreas Gross (Social Democrats). Both were active in the GSoA in the 1980s and went on to become influential figures in Swiss national politics.

But challenges also exist. At the end of the 1990s, the NATO mission in Kosovo split the GSoA. A second initiative to abolish the army in 2001 garnered only 22 percent of votes in favour; many regarded the initiave as an obstinate course of action. The current situation with the Russian war against Ukraine is not easy. The GSoA has so far rejected the idea of Swiss military support for Ukraine but criticizes Switzerland’s role as a financial centre and raw materials hub that permits Russia to make financial profits that go to feed its war economy.

The Left rejects joining NATO, especially the GSoA, but also the Greens. The Social Democrats are not entirely categorical about this issue. The party with the largest share of votes, the right-wing nationalist Swiss People’s Party, even claims that Switzerland can, and should, be able to defend itself alone. Therefore, there is no majority for joining the alliance. Surveys indicate that such a move to NATO would also be unpopular among the population. Neutrality has a long tradition in Switzerland and is valued by all; joining NATO would be a break with this. Nevertheless, a rapprochement is under way: one sign is the purchase of 36 F-35 fighter jets for six billion Swiss francs. These planes were chosen because their systems are compatible with those of NATO.

Jan Jirát is a journalist for WOZ, Die Wochenzeitung

The article has first been published in the Atlas of Disarmament