Share Twitter Facebook Email Copy URL

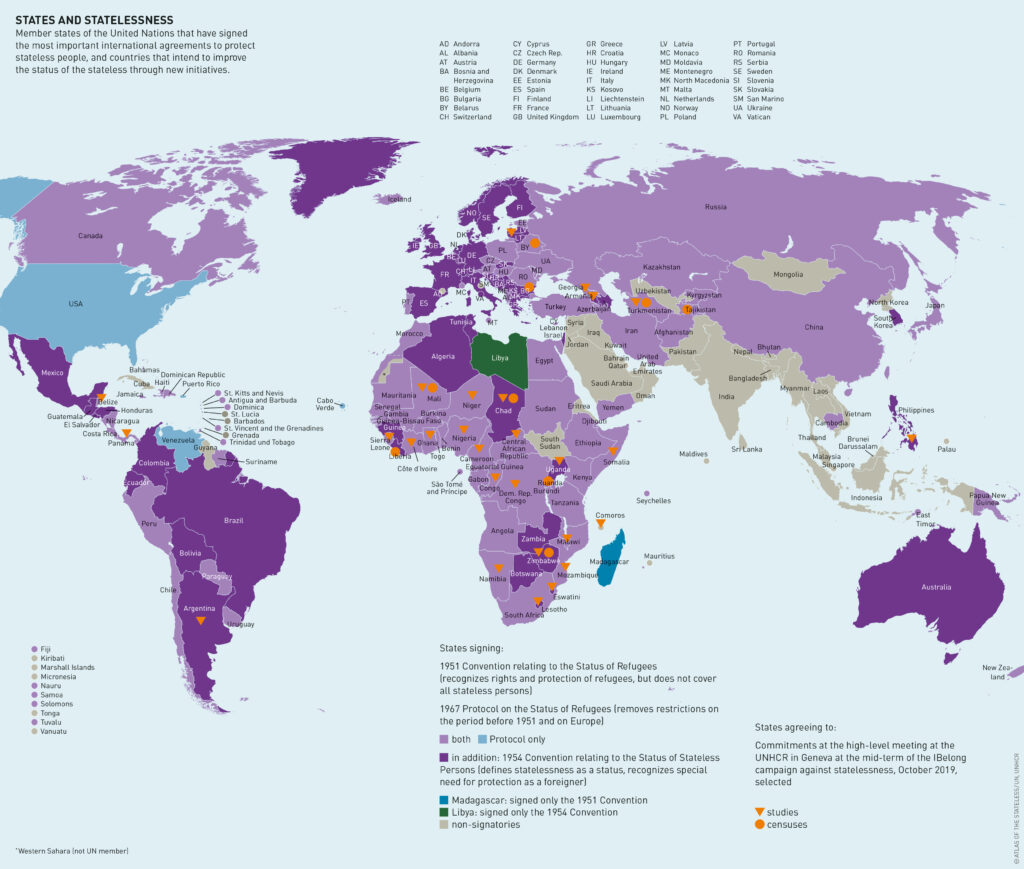

States grant their nationality to individuals, but they follow different sets of rules, and sometimes apply those rules in ways that lead to statelessness. International law has tried to plug the gaps, but less than half the world’s countries have signed up.

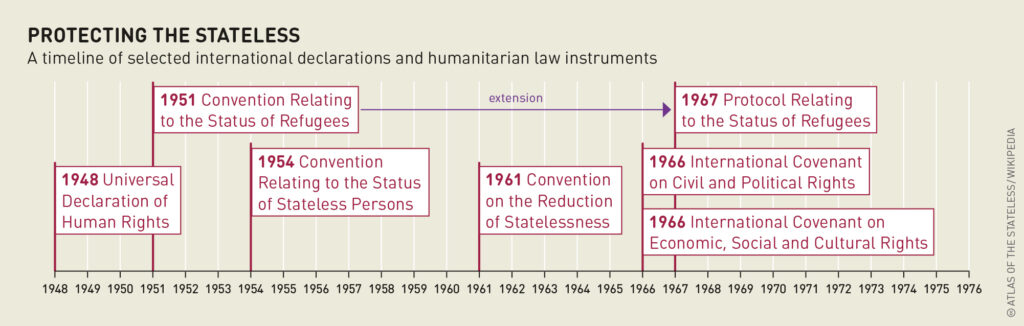

The rights and status of stateless individuals are covered mainly by two international conventions: The 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons and the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness. The 1954 Convention defines a person as stateless if he or she is “not considered as a national by any State under the operation of its law”. Statelessness is defined as a legal status that depends on the laws and regulations made by states. Nationality and statelessness are thus two legal concepts that mirror each other. Neither the international community nor the United Nations can grant a specific nationality to a person; only states have this power. The definition also implies that it is the state, not the individual, that decides a person’s nationality.

But what matters is the actual operation of a law, not only the wording. State authorities may consistently apply a particular provision in their nationality legislation in ways that diff er from the wording of that legislation. They may do so for reasons of racial, ethnic, religious or political discrimination. The actual practice needs to be taken into account in determining a person’s nationality status. Moreover, the wording “considered by a state” requires an actual decision by a state’s officials on the nationality status of a person before he or she can be called stateless.

have not yet signed any international treaties

for the protection of stateless persons

But not every unregistered or undocumented individual can be considered as stateless. In fact, the vast majority of unregistered or undocumented persons are nationals of a specific country, most frequently the one where they were born. They may be of undetermined nationality, perhaps at risk of statelessness, but legally they are not considered stateless until a state official has denied them the nationality that they claim. As far as the definition uses the notion of nationality, “nationality” and “citizenship” are synonymous.

While the 1954 Convention currently has only 94 State Parties, many of its core provisions have crystallized into customary international law. The definition of the term “stateless person” may thus be seen to be legally binding upon all states, irrespective of their accession to the 1954 Convention. Apart from that, the 1954 Convention guarantees certain human rights to stateless persons, such as the freedom of religion, access to courts, right to work, and access to public education.

However, these rights are essentially construed as state obligations, not as individual entitlements. Moreover, the protection level of the 1954 Convention often falls short of international human rights granted in later treaties, such as the standards defined by the two 1966 International Covenants on Civil and Political Rights and on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

The 1954 Convention stipulates certain rights on the lawfulness of a stateless person’s stay in the country. It is the only one that universally provides for the status of stateless persons, defines the legal meaning of statelessness, guarantees basic human rights for stateless persons, obliges states to issue identity papers and travel documents to them, and foresees the possibility of their naturalization. As such, the 1954 Convention has retained its crucial role for the protection of stateless individuals.

Various international human rights documents, starting with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, protect the individual human right to a nationality. However, none of these are sufficiently concrete and operational to stipulate the obligation of a specific state to grant its nationality to a particular person. This legal gap is filled by the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness. In other words, this Convention defines state obligations to grant nationality.

making new treaties to protect human rights,

but on making sure they apply everywhere

The 1961 Convention starts from the fundamental principles that a state should grant its nationality (1) to a person born in its territory who would otherwise be stateless; and (2) to a person not born in its territory, if one of his or her parents was a national of this state and the person would otherwise be stateless. Foundlings should acquire the nationality of the state where they are found.

Additionally, the 1961 Convention aims to ensure that a loss or withdrawal of nationality does not create statelessness. Accordingly, a state shall not deprive a person of his or her nationality if such deprivation would render him or her stateless. Marriage or any change of personal status may not lead to the loss of nationality if the affected person would thereby become stateless. Spouses and children may only be affected by a person’s loss of nationality if this does not render them stateless. And last but not least, the deprivation of nationality shall never be based on racial, ethnic, religious or political grounds.

political, racial, ethnic and religious

grounds – or because of a change of territory

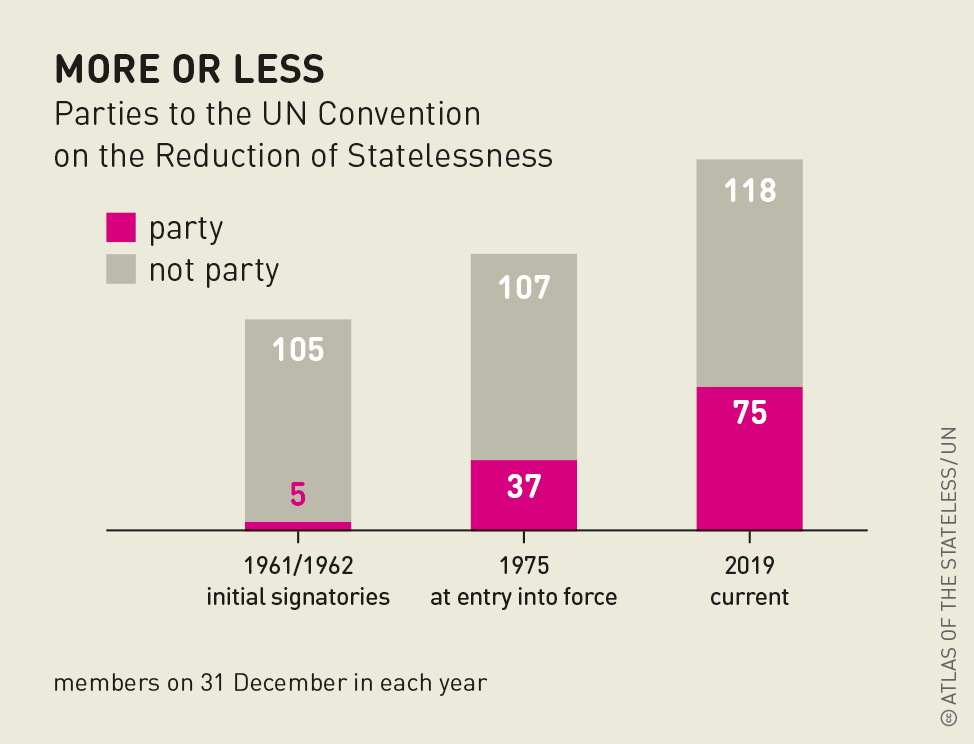

The 1961 Convention currently has 75 state parties. While accessions have increased in recent years, there is still a long way to go towards universal backing. However, even in those states that are not party to the 1961 Convention, the instrument provides authoritative guidance on how to respect, protect and fulfill every human being’s right to a nationality.

This contribution is licensed under the following copyright licence: CC-BY 4.0

The article was published in the Atlas of the Stateless in English, French, and German.