Share Twitter Facebook Email Copy URL

Reflections following UN CSW 67

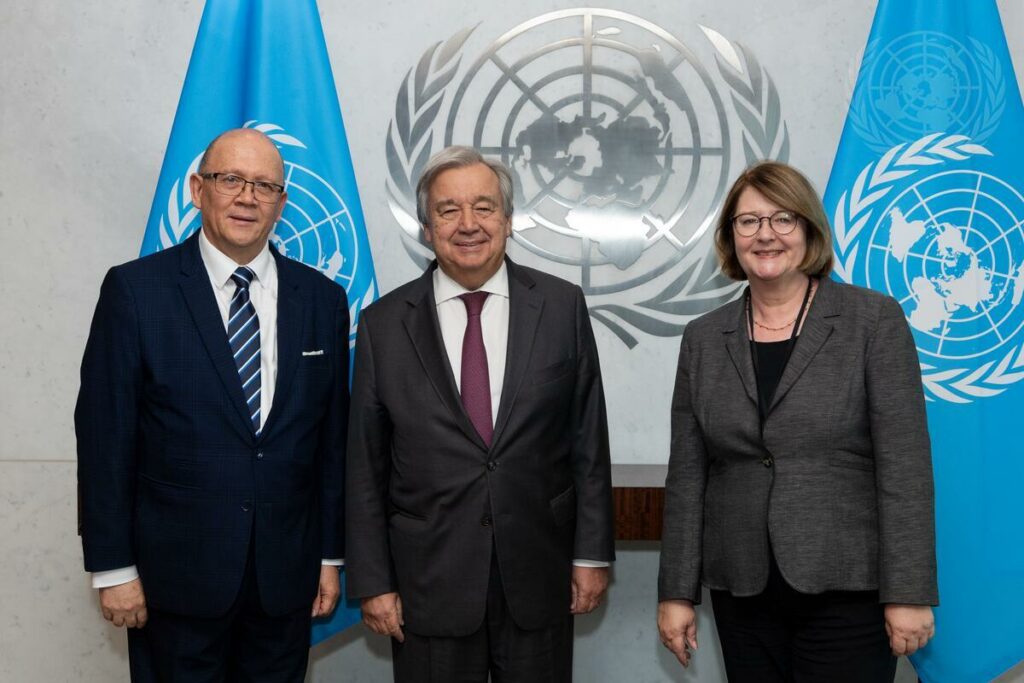

Innovation, technological change, and education in the digital age for achieving gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls: this was the topic of the 67th Session of the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women (UN CSW67[1]), which met in New York from 6 to 17 March 2023. The Commission is the only global cross-governmental body dedicated to the promotion of gender equality and women’s empowerment. This year’s was the first meeting since the 2020 suspension due to the pandemic. It recorded very high attendee numbers with more than 7,000 participants, thus confirming itself as the United Nations’ event patronised by the largest number of non-governmental organisations.

In recent years, technological transformations have revolutionised, globally, every aspect of individual and collective life, overwhelming it at increasing speed. A seemingly unstoppable tornado, in terms of both time and space. A cyclone that is able to capture and subdue the minds of people of all ages and latitudes. A hurricane that finds its way into everything, but that is exempt from mechanisms of transparent knowledge and democratic participation. With the advent of the digital age, both the organisation of work and daily life have been profoundly transformed. Suffice to think of the acceleration experienced by virtual communication as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, from 2020. Increasingly, we need to face new emerging challenges, in political, social, economic and environmental terms.

Recurring rhetoric only emphasises the actual or potential development opportunities provided to society by digital applications, artificial intelligence and new platforms. This narrative overlooks the emerging phenomena reproducing former inequalities and discrimination, in many cases aggravating them, or even creating new vulnerabilities, especially in the world of work. Little is said about who, where, how and for what purposes algorithms are conceived and the ways in which they define decision-making mechanisms, and which are beyond democratic control.

Platforms are often celebrated as a viable alternative offering flexible and affordable work for those who have family. However, in fact, in daily practice, they enhance disparities in the distribution of care activities, since it is mostly women who choose to use them in order to work while staying at home. On the other hand, the development of platforms for family services, such as food delivery, childcare and household cleaning, is often of a precarious nature, as, once again, these jobs are mainly carried out by women, not infrequently with poor protection and difficulties in having even their fundamental rights recognised. Thus, there is the risk that even the virtual world will confirm, or even enhance, the patriarchal model of society, reproducing the gender pay gap that historically has tended to reduce more slowly than other inequalities and condemns women to greater poverty even in old age. In fact, for older women, digitalisation is already, and can further represent, a real factor in increasing exclusion rather than inclusion, even for accessing basic essential public services, if it is not accompanied by the consideration of what is necessary in terms of benefits, education and care.

These are widespread phenomena taking place globally and in almost all countries. According to the Online Labour Index (OLI), which is the first international economic indicator measuring the gig economy online, between 2017 and 2021 the online job offer increased by 150%. It’s not easy to quantify how many female workers are affected, as the data is not disaggregated by gender and no surveys are carried out in this regard. However, what also certainly emerges from the latest available research (ILO WESO 2021[2]) is that: equality between men and women at work is lagging behind and the historical achievements on equality are compromised, new segregations are emerging and cases of gender-based violence growing. In other words, we are witnessing the repetition of historically structured forms of gender exploitation and oppression, with ‘new’, intersectional class divisions, such as by age, disability, migrant status, indigenous status, occupation, profession or educational qualification. A thorough structural analysis of gender inequalities and their causes, at the origin of a devastating vicious circle, is needed in order to question the patriarchal power structure on which they are based.

In light of the above, it’s clear how relevant was the debate that took place at CSW 67 on these issues affecting democracies at their heart and the search for social justice. Even just being able to talk about the economics of platforms, automation and digitalisation has been a significant achievement. The Commission on the Status of Women met against a background of continued attacks on women’s rights at the global level, increased violence in the public space and gendered impact of climate change and earthquakes in Syria and Turkey, in addition to the daily horror experienced by women and girls in emergency and crisis settings, such as in Afghanistan, Ukraine and Iran.

A compact, strong and forward-looking feminist response by the UN Commission on the Status of Women, involving an authoritative stance on rights and freedoms, was expected, i.e., needed. But perhaps, today, such a response would only have been possible in Neverland! This year, the CSW session was characterised once again by a difficult political climate, similarly to that in the last years before the pandemic, involving forceful struggles between governments and sides, especially on language and rights. Civil society and trade unions played a lobbying role, providing government representatives taking part in the session with their proposals for amendments to the texts, supported by substantive arguments in favour of inclusive language and content. Finally, governments agreed on a document, the so-called agreed conclusions, containing arguments of undoubted interest requiring careful assessment. First of all, it acknowledges that the achievement of gender equality and the empowerment of all women in the digital age is an essential need for sustainable development, the promotion of peaceful, just and inclusive societies, economic growth, as well as for ending poverty in all its forms and sizes. At the same time, it expresses concern about a series of issues, such as limited progress in bridging the gender gap in the access and use of technologies and digital literacy. It recognises the consistency, increase and interrelationship between offline and online violence, harassment and discrimination against women and girls. It highlights the need for inclusive and equitable quality education in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. It reiterates the importance of implementing the International[3] Labour Organization’s decent work agenda through the adoption, promotion and implementation of core labour principles and standards.

In New York, governments reasserted the universal and interdependent character of the promotion, protection and respect of the human rights and fundamental freedoms of all women, including the right to development, and that they are essential for the purposes of the full and equal participation of women in society, as well as their economic emancipation. Measures are now needed in order to ensure the enjoyment of these rights. Indeed, it is significant that governments have explicitly acknowledged the need to ‘significantly’ increase public and private sector investment in order to have more inclusive innovation ecosystems and promote safe technologies and innovations able to meet gender needs.

Words are important and have weight. Now, without delay or hesitation, it is down to the same governments to translate them into concrete decisions and actions, in order to consistently follow up the work of the Commission and avoid undermining their own credibility and that of the multilateral bodies created with the aim of building and defending peace, democracy and justice in the world.

Silvana Cappuccio is an expert in international trade union policy. She is working in the SPI CGIL International Policy Department, is titular member of the EU OSHA in Bilbao and have represented the three Italian trade unions CGIL CISL UIL in the workers group of the ILO during the last seven years, until June 2021. She is the author of two books: Glokers – People, Places and Ideas about Globalised Labour”, in Italian, and “Jeans to Die For” (about silicosis in the jeans production industry), in Italian and English.

[1]The United Nations Commission on the Status of Women is a functional organisation of the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), established in 1946.

[2] International Labour Organisation World Employment and Social Outlook, ILO WESO 2021 The role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work, 2021 World Employment and Social Outlook (ilo.org)

[3]The ILO Decent Work Agenda is based on an integrated and gendered approach based on four pillars: productive and freely chosen work, labour rights, social protection and social dialogue Decent work (ilo.org)