Share Twitter Facebook Email Copy URL

While most readers of this Atlas have the pieces of paper, booklets and plastic cards that permit them to get money from a cash machine, consult a doctor, travel, drive and vote, that is not the case for stateless persons and other marginalized groups.

In 1949, from her exile in New York, the Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt formulated “the right to have rights”. For Arendt, this meant the right to belong to a politically organized community and to be judged by one’s actions and opinions. This was the summary of her personal experience of statelessness, which began in 1937 with the Nazi regime and lasted until 1951. She described not only the loss of human rights of the millions of Jews murdered by the Nazis, but also the painful experiences of millions of people in exile.

The widespread appearance of stateless people in the wake of the two world wars led the idea of human rights to an absurdity. According to Arendt, the “aporia (internal contradiction) of human rights” comes about because only citizens can claim them. As a result, Arendt said that stateless people were “worldless”. They had not only lost their home, but also could not find a new one anywhere else. Exclusion from the social fabric and the functional systems of society throws such people into the inhuman status of “superfluousness”.

The horrors of the Second World War led to the creation of the United Nations and to a redefinition of human rights in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948. The experience of stateless persons also resonated here. Article 13 of the Declaration affirms the right to move freely within a state, to leave a country, and to return to one’s own country. Article 14 grants the right to asylum from persecution. Article 15 provides that everyone has the right to a nationality.

But, according to Seyla Benhabib of Yale University, the articles in the Declaration of Human Rights do not guarantee a right to naturalization or membership in a political community. International law is based solely on the agreement of sovereign nation-states, and are enforceable only against them. For Arendt, the contradictions between sovereign rights, transnational legal claims and human rights norms pointed to the conclusion that the number of refugees actually covered by human rights was too low. Therefore the proclamation of human rights had, for Arendt, little to do with the fate of genuine political refugees. She called for the right to be a member of a political community for everyone.

Without the right to have rights and to belong to a political and social community, other human rights are void. This is true for stateless persons and for all of those who have been disenfranchized: people without papers, minorities without access to rights, refugees without residence status, the homeless, unemployed and exploited. According to Arendt, people are not born as equals, but are made equals as members of a group by virtue of the decision to guarantee equal rights to each other.

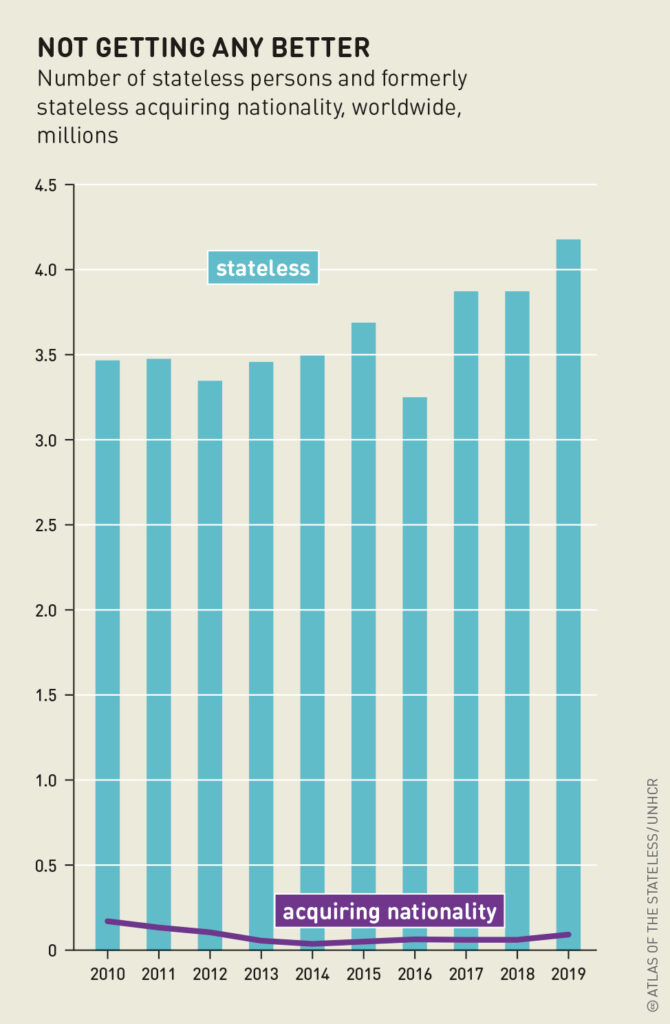

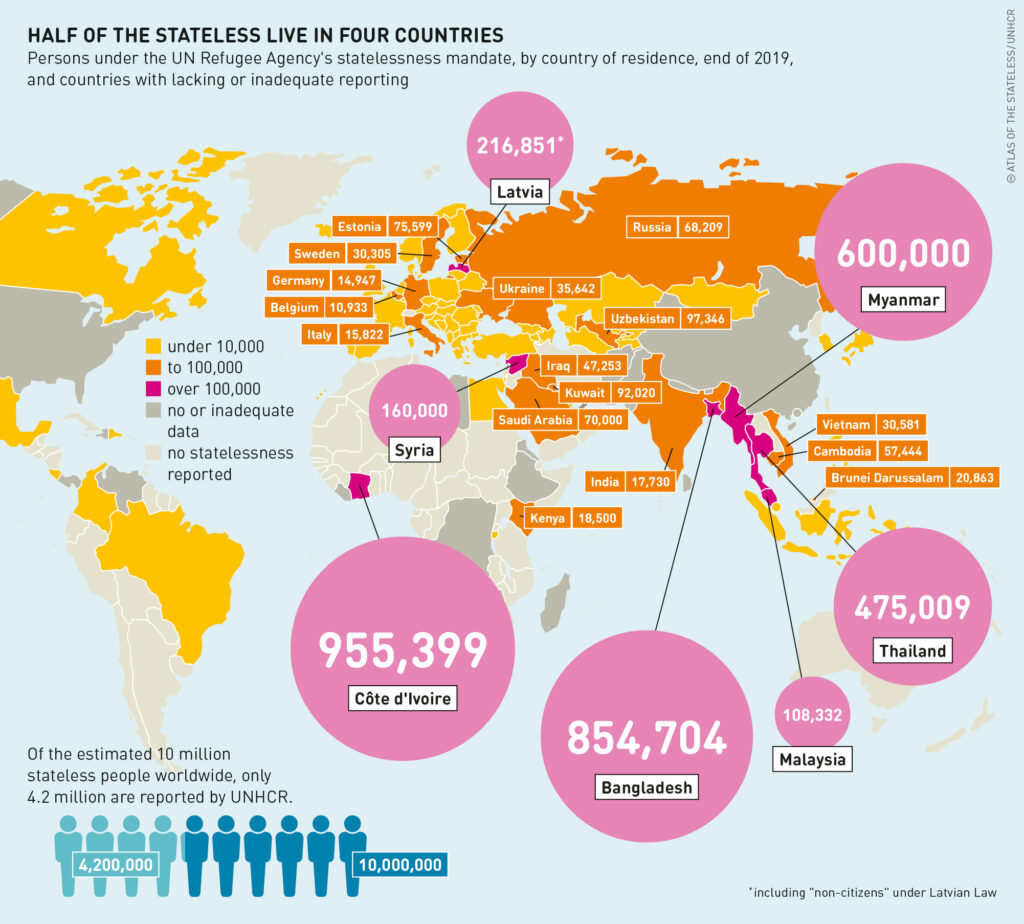

citizenship in the last ten years. The bad news:

more than four million people are still waiting

Human rights are not in themselves just or inclusive. Human rights are rights of resistance against all forms of injustice and oppression. These have been constantly renegotiated and fought over for centuries. This was true especially for the labour movement, which has always linked its political struggle with the demand for legal rights. In view of the current danger that governments and political parties are instrumentalizing human rights in order to demand exclusivity and even to justify war, the “right to rights” is about renegotiating rights.

For Stephanie DeGooyer of Harvard University, the struggle is above all about the right to be a member of a community that offers justice. Human rights must be regarded and employed as a political practice. Nationalist movements and parties try to link human rights to the nation-state, selectively reserving rights for a particular ethnic group, thereby creating an artificial sense of community that is based on exclusion. Arendt argues that true democracy can exist only where the centralized power of the nation-state is broken. Democracy is the active participation in, and the co-determination of societal and political decisions. This participation presupposes the right to have rights, and so the entitlement to a place in society.

that many more people

around the world are stateless

The current situation of stateless persons and people without rights around the world brings new relevance to Arendt’s demand for “the only right”. The issues at stake here are the social and political options for action and participation that enable the “worldless” to escape from their situation and regain their ability to act, their identity and their human dignity. Governments and social movements are jointly responsible for refuelling the concept of human rights for self-empowerment of the disenfranchized with emancipatory and political energy. That involves showing solidarity with the “worldless” and the disenfranchized, as well as giving up their own privileges and power. The commitment to a just society, the solidary responsibility of the community for the individual, requires a redefinition of human rights as rights of resistance.

This contribution is licensed under the following copyright licence: CC-BY 4.0

The article was published in the Atlas of the Stateless in English, French, and German.