Aktie Twitter Facebook Email Copy URL

An initial assessment of the outcomes at COP26 – in englischer Sprache!

Katja Voigt is a Senior Advisor for Climate Policy at the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Berlin.

Uwe Witt is a Senior Advisor for Climate Protection and Structural Change at the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Berlin.

David Williams directs the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung’s Climate Justice Programme in New York.

Till Bender is a Senior Advisor for International Politics and North America at the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Berlin.

The article was first published on rosalux.de.

Esplanade – COP26 Coalition Rally Photo: Stephen and Helen Jones, CC BY-SA 2.0

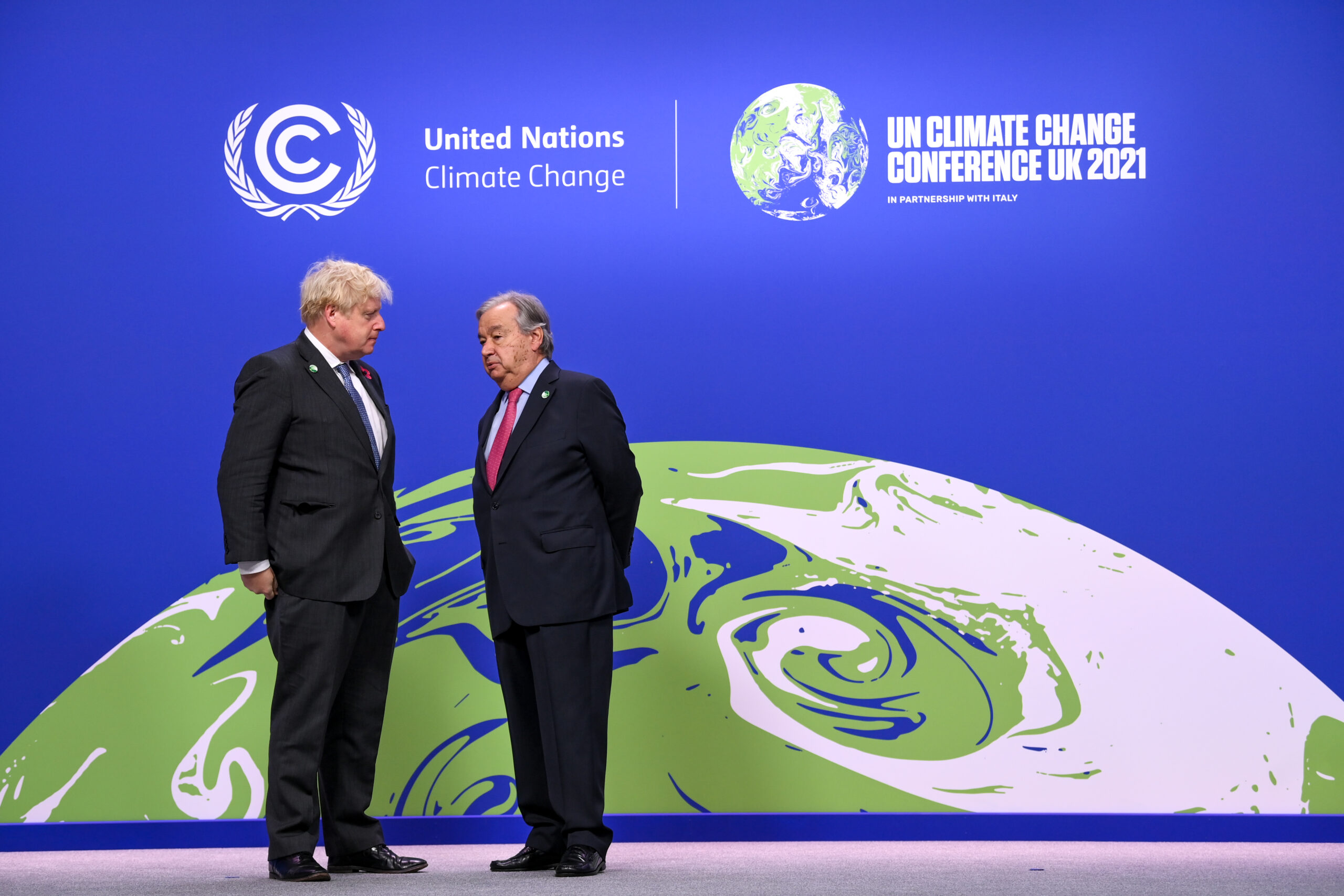

There were high expectations for COP26 given the scientific evidence for the climate crisis as well as the urgent need to keep global warming in check and, at the same time, address the impacts on populations who have contributed the least to the problem in particular. What we actually heard, however, were a lot of promises and compromises, with nations pledging small contributions while depicting them as huge commitments.

While there have been small advancements regarding several issues, governments at COP26 missed the chance to display real commitment to both adequate climate action and justice in international climate policy. Access to the official negotiations at COP26 was more unequal than ever before, and delegations and activists from many countries from the Global South were missing in Glasgow.

There were plenty of opportunities for parties to shine and really promote multilateral climate policies — for instance, by responding to the call from many countries of the Global South for adequate and proper funding for losses and damages caused by the climate crises already occurring in their respective regions. Due to the pressure by social movements and countries of the Global South, loss and damage received a prominent profile at COP despite not being an official agenda item. Some progress was made towards agreeing on the functions and funding for the Santiago Network on Loss and Damage, that was created in 2019 to provide technical support to countries dealing with climate disasters, but so far has only existed virtually. The Glasgow Climate Pact, however, does not go far enough to initiate and resource a new Loss & Damage facility as demanded by developing countries and civil society.

Parties also could only agree on a rather vague higher commitment to increased adaptation finance. Rich countries came to COP26 admitting they had failed to meet their promised collective goal of providing 100 billion US dollars to developing countries per year by 2020. What they did not say is that they delivered 70 percent of that climate finance in the form of loans and investments instead of grants, raising the debt burden of the recipient countries. While COP26 agreed to double adaptation finance, it is again unclear whether this money will be additional or recycled from other insufficient sources such as development and humanitarian aid. The development of a new collective goal on long-term climate finance, to kick in beginning in 2025, was formulated only vaguely in the Glasgow Climate Pact.

The final decision stresses the need to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 45 percent by 2030 compared to 2010 levels to be able to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees. According to the countries’ reduction commitments (the National Determined Contributions, NDCs), however, the emissions will lead to an increase by 16 percent by then, which would lead, according to scientific calculations, to a warming of 2.7 degree by the end of the century. Stringent action has been postponed into the future.

Germany is also one of the culprits: the new administration appears to be unwilling to take effective steps, especially in the areas of transport and heat. Germany’s refusal to join the Joint Statement of the Zero Emission Vehicle Transition Council in Glasgow (a commitment to phasing out the internal combustion engine by 2035) illustrates this reality. Moreover, Germany as a whole lacks a concept of how to ensure that the transition is conducted in a socially just way, while the exceptions for industries have for the most part already been worked out in great detail.

With the outcome of Article 6, the role of carbon markets in climate action — and with it the finalization of the Paris Rulebook — we again have market instruments “regulating” carbon emissions. The decision on market and non-market mechanisms were finalized with much uncertainty and details which remain largely undefined. While it was celebrated that the new regulations will avoid double-counting and a — rather weak — reference to human rights as well as social-environmental safeguards are included, there might still be loopholes that could lead to ever-increasing emissions.

Coming into Glasgow, COP26 was hyped as the “Net Zero COP”, with the UK COP Presidency pushing for “net zero by 2050” declarations from governments and corporations. Civil society challenged and debunked the oversimplified framing of “net zero by 2050” as allowing business-as-usual for decades, and relying heavily on carbon offsetting instead of real transformation to actually bring greenhouse gases down to zero.

Throughout the two weeks in Glasgow, several interesting initiatives were presented, among others the US-China Joint Declaration on Enhancing Climate Action or the initiative to reduce methane emissions. These are, however, neither binding nor is it clear what their implementation might look like — and they may have been more of a distraction from the actual negotiations.

During the closing plenary, when parties had the final opportunity to intervene, it was noticeable that none were entirely comfortable with the agreed text. The final decision mentions important concepts such as just transition, and for the first time ever, fossil fuels have been referenced in a COP decision text. Language was watered down at the last minute, and India was vilified by demanding for a “coal phasedown” instead of a total “phaseout”.

This intervention, however, needs to be seen in the larger context of equity, with India still having very low per-capita emissions and high poverty rates. No doubt that we need a “phaseout” instead of a “phasedown” — but the Glasgow Climate Pact does not make any commitments to help developing countries move away from coal and invest in greener energy pathways. Given the lack of finance and the issues of equity, while allowing rich countries to avoid shifting or providing finance, the question is how adequate and, at the same time, fair the Glasgow Climate Pact language on fossil fuels really is.

The disappointment concerning the outcome, especially from civil society, could be seen in several protests for climate justice inside and outside the negotiation hall. Several protests and activities took place in Glasgow and around the world to pressure governments to commit to higher climate action. The Fridays for Future demonstrations as well as the Global Day of Action for Climate Justice brought tens of thousands of people onto the streets of Glasgow. At the People’s Summit for Climate Justice, organized by the COP26 coalition, people came together to share their stories from the ground and discuss climate just solutions, including indigenous knowledge as well as visions for a feminist global Green New Deal. The expression of solidarity and understanding of the gravity of the situation made this summit an important space for alternative approaches promoting a true system change.

Time will tell whether the COP26 decisions will be put into action. Until then, it’s important that we as a civil society continue to raise the concerns of those most affected by the climate crisis and fight for climate justice. As part of this commitment, we will soon be publishing a detailed report on the outcomes of COP26 and where to go from here.